America Rediscovered [by James Wenley]

It is very subtle, and depending where you are sitting, invisible. Etched onto the stage floor is one of the most famous sentences from world history: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights…”

For his final offering as Artistic Director of Silo, Shane Bosher has given the people of Auckland Tony Kushner’s two-parter Angels in America. A play eight years older than the company Bosher has led for the last thirteen years, performed in a venue (next door to his old stomping ground) that didn’t exist when he first started, Bosher has been preparing the way for some time.

Part One: Millennium Approaches is a moment in time and place. Written by Kushner in the late 80s and debuting in 1993, it is set at the end of 1985. In this vision of America, the only Declaration of Independence-type equality is that death comes to us all. In the arms of the Reagan administration, republicans look forward to a vision of enduring rule and exceptionalism; “America has rediscovered itself”. Meanwhile AIDS and its horror are ravaging the gay community. Harper Pitt, a Mormon housewife, obsesses over the hole in the ozone layer. As a millennial play it has more than a hint of impending apocalypse: “the world is coming to an end”.

One of the many provocative theses espoused within the show is that in America, there’s only the political: “no gods here… no angels in America, no spiritual past, no racial past”. Is the “Creator” named in the Declaration merely a political creator? Are Americans a people without souls, political power being the only end-game?

Kushner’s opus is a stunning dissection and disintegration of 1980’s America. Its insightful on the Reagan mentality, its characters fascinate, and its humour has a wonderfully dark, sharp (and occasionally camp) edge. But this is America as it was. Who worries about ozone hole these days? The landscape has shifted: Russia checkmates America over Crimea. Privacy is dead. The hole in the Ozone is the least of our climate problems. Arguably America is as diseased as ever. With greater distance in time, and place, Bosher needed to find something else within the play to make us care. The answer is timeless: people; the responsibility of care towards one another, and the gulf of understanding. The individual, set against the community, set against the nation. It is still a play for our times.

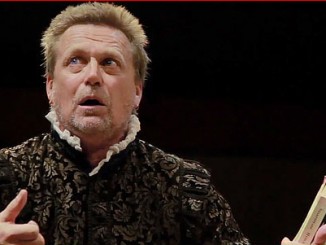

We watch them struggle, bleed, and grapple with what lies behind their existence; where are they going, why, who with? Jo Pitt (Matt Minto). Lawyer. Mormon. Gay (closeted). Husband. / Harper Pitt (Chelsea Preston Crayford). Mormon. Wife. Vallium Addict. / Hannah Pitt (Alison Bruce). Mormon. Mother. / Louis Ironside (Dan Musgrove). Gay. Jew. / Prior Walter (Gareth Reeves). Gay. Dying. / Belize (Jarod Rawiri). Gay. Drag Queen. Nurse. / Roy Cohn (Stephen Lovatt). Lawyer. Powerbroker. Gay. Dying of AIDS.

No, wait. In an intense antagonistic rejection of his doctor’s prognosis, Roy Cohn attacks: “Your problem… is that you are hung up on words, on labels, that you believe they mean what they seem to mean”. Cohn, a historical figure famous for being a Senator McCarthy acolyte, refuses this identity, because he has clout. “Aids is what homosexuals have, I have liver cancer”. Kushner uses these given identity types to build, complicate, and transform his characters. In living in the individualistic 1980s, all are suffering an identity crisis.

For the actors, these parts are heaven sent, and it is in his work with the actors that Bosher’s hand as director truly shines. The performances are ‘across-the-boards’ exceptional: with this demanding play and director they’ve been pushed right to their limits, then told to push further. Some of the standouts: Alison Bruce’s metamorphosis as a truth-telling Rabbi. The palpable venom in Stephen Lovatt’s eyes as Cohn tirades. Chelsea Preston Crayford’s breakneck mood shifts. Gareth Reeves’ melancholy as disease begins to take hold. Matt Minto’s release as he admits his hidden self. Minto and Lovatt’s outrageous double act as Walter Pryor’s distant ancestors come to visit. The actors acquit themselves ferociously and fearlessly, and are one of this play’s greatest pleasures.

Kushner’s play text includes little prescription. He writes that “the play benefits from a pared-down style of presentation”. The “moments of magic” in the show are to be produced as “wonderful theatrical illusion – which means it’s OK if the wires show, and maybe it’s good that they do, but the magic should at the same time be thoroughly amazing”. Bosher has taken this directive to heart, and in true Silo style, paired the play back even further. No need for desks when characters can hold telephones (the old corded kind) in their hand, and two moveable rectangular slabs can stand for a whole host of things. When set pieces are needed: hospital beds, executive couch, trolleys of homeless detritus, they make a statement. Rachel Walker’s set is dominated by a sheer wall, segmented by different patterns of dripping black paint, placed to push the action right forward, with the floor in front open for possibility. I catch brief glimpses side of stage of actors and crew coming and go, snatches of what lies beyond the wall in Plato’s Cave. Bosher makes his own statement early – both in style and symbol – we watch as the actors scatter and blow crisp dead leaves across the stage, which produces a satisfying crunch each time the actors walk over them in the first act. The stage is later covered by a dark snowstorm (dark, slightly translucent confetti flicking evocatively in the air and delicately captured by Sean Lynch’s Lighting Design). It is only blood that is too easily wiped away by a stage hand immediately after the letting, consequence free.

It’s a design that seems to make its statement in simplicity, but holds a great deal of surprises: openings and pits to achieve those moments of wonderful theatrical illusion as characters, including an Eskimo in Antarctica (yes indeed!), appear and disappear in moments of hallucination and magic realism. The biggest of the set’s surprises is saved for a climatic, cracking ending, a cliff-hanger that gets you well and truly pumped for Part Two.

It’s interplay then of restraint and lurches of exuberant expression, a fantasia of modes and tones that Bosher conducts superbly. Bosher approaches split scenes, such as the breakdowns between Joe and Harper Pitt, and Prior and Louis with the same eye he bought to Bovell’s When the Rain Stops Falling and Speaking in Tongues, discovering connections as he moves the bodies through space. When one couple erupts, the other descend deeper into their tense silence.

The costumes by Elizabeth Whiting are a perfect match of character and style ranging from Joe Pitt’s suit, intentionally non-descript so as not to call attention to himself, to the outrageous flourishes of Harper’s hallucinatory travel agent Mr Lies (Jarod Rawiri) with pimp fur coat and chunky red trainers.

For everything that works – as so much in this production does – the few elements that don’t stand out. For every time Leon Radojkovic score is richly foreboding (capturing the huge thunk of impending angel wings), it’s also generic and flat. The digital beeps in Roy Cohn’s first scene, though called for in the script, overwhelm and grate. The sound mix drowns out Mia Blake’s lines as the angel, and while HBO comparisons are fruitless, with all the anticipation I did feel underwhelmed at a key moment by the immediate impression of her angel’s visual design. I await Part Two to hopefully change my mind. For a production that cancelled its previews due to technical problems, all other aspects were masterfully assured.

Harper, in a moment of valium-induced clarity, muses that we cannot know the unknowable. Everything is just permeations of the same: “It’s really the same old ordinariness and falseness re-arranged into the appearance of novelty and truth”. If so, with Angels in America, I’ve deluded myself. Because to my eyes, this is no ordinary play, and in Silo’s hands, it has a great many urgent truths to tell… and dispel.

Totally gripping, those three hours fly past all too fast. Thank the heavens there is more yet to come!

Angels in America Part One is presented by Silo and plays at Q until 13 April. Details see Silo.

Leave a Reply