[Representation Matters]

Silo Theatre’s production of Mr Burns presented a vision of theatrical futures. In the play by American writer Anne Washburn, survivors of an electricity-ending event band together to form a travelling theatre troupe specialising in the recreation of classic The Simpsons episodes.

I begin with Mr Burns here because, while it presents a bleak image for our planet, it is hopeful about the endurance of theatre. The third act of the play is a marvel: the action skips forward 75 years and we are presented with a play-within-a-play that returns to the roots of Greek drama by way of Grand Opera while using the Simpsons characters to dramatise the apocalyptic event that occurred decades before. Washburne’s play speaks to our need to be together to watch and perform stories in order to try to understand the world, where we’ve come from, and where we’re going.

Of course, the play also provides some commentary on neoliberal entertainment competition – act two portrays a Mad Max theatre land where a rival company, wanting to steal your scripts, might storm your venue and open fire.

Most concerning of all perhaps was what Silo and designer Daniel Williams did with the venue, giving us a vision of a trashed and abandoned Q Rangatira, a seating block fallen into a pit.

Recalling theatres Auckland has lost (including the yet to be reopened St James), this image was a reminder of just how precarious the theatre industry can be. But also, how necessary. The warning raises a question of how to sustainably nurture the theatre ecology and work together.

This did not always happen in 2018. This was a year defined by drama offstage as much as on, with the theatre industry receiving a considerable amount of media attention and not always for the right reasons. This year’s Theatre Scenes annual review is front-ended by a variety of divisive controversies.

#MEWHO?

Theatre is a space of representation. Set, props and actors can be stand-ins for the real world; productions variously draw you into the illusion, or draw attention to the unreality of the representation. A founding principle (albeit one made to be broken) is that the actor is not themselves – the actor plays a character. The actor, in theory, can represent anyone. But this is elasticity is challenged by another important aspect of representation – whose stories are being told, and by whom?

The representation and diversity debates rippling through global entertainment and societies are especially pertinent to the embodied liveness of theatre where audiences and actors face each other in the same room. Who are the playwrights, directors and theatre-makers getting funded and programmed? Who are the actors? Who is the audience? Who is included, and who is excluded? Who has the power?

This year the Pop-up Globe was a site where these issues of representation flared up and rocked the national theatre community.

The Pop-up Globe, led by impresario Dr Miles Gregory, has been the highest profile new entrant to the Australasian theatre market in recent years. At the start of 2018 their third season of Shakespeare was playing at the Ellerslie Race Course, following a triumphantly successful season in Melbourne.

When the Pop-up Globe venture was first announced, one attached project was an all Te Reo version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. While this never eventuated, the idea was transmuted into the Pop-up’s latest production of Midsummer, which featured the play’s fairy sections translated into Te Reo. The Pop-up Globe was able to ride the wave of Te Reo revivalism and gain positive PR from an Don Brash-esque audience backlash, but by the time I saw the production late in the season they seemed to have lost their nerve with some fairy verse returned to the Elizabethan original. While their use of Te Reo is laudable, the company’s ‘wokeness’ was rather undercut with Gregory’s production of The Comedy of Errors, which traded on orientalist tropes and “fancy dress”. In a since deleted tweet, Gregory insisted that “the play and production is set in Ephesus, in Greece, in the 17th century. Not sure where the herald got ‘oriental’ from. Not our words.” Curious then that the show began with the cast holding machine guns garbed in ISIS style-uniforms, evoking Middle Eastern terrorist stereotypes. If there was one image that represented the 2018 season for me it was the drunk Porter in Macbeth, taking the popular groundling ‘splash zone’ to the next level by pissing on the audience. Midsummer, Merchant of Venice, Macbeth and Errors went on to represent us in Sydney.

One addition to the Auckland season was a majority-female production of Julius Caesar directed by Rita Stone (the two men in the cast spent much of the production in chains, a pointed twist on female subjugation and masculine anxieties of matriarchal power). While a controversial New York production evoked Trump, here Donogh Rees’ Caesar was a pant-suited Hillary type. One of the most fascinating aspects was the regendering of the language (a “there is a tide in the affairs of women”), making visible the normative masculine associations of leadership. Unfortunately (and tellingly), this production was a given a lesser status than the other four plays, playing off-nights over a truncated season.

As had become Pop-up Globe tradition, two of the productions (Midsummer and Merchant of Venice) were performed by an all-male troupe. Well, almost. Near the end of the season it was revealed on Seven Sharp that one of the actors was female cis gendered but passing as a male. What this experiment was meant to prove is unclear. The arbitrariness of gendered concepts? The bravura performance of an actor able – to borrow from Viola and Iago – to act “not as I am”? Putting aside the responsibility placed on the sole female actor, USA’s Sarah Griffin performed one of my favourite ever renderings of Portia.

A lesson it did not seem to teach the Pop-up Globe decision makers was the foolishness of excluding female actors from the stage. In July came the press release announcing a fourth Pop-up Globe season. POP-UP GLOBE ANNOUNCES MOST CONTROVERSIAL SEASON YET. Boy, would that prove to be an understatement. The overall theme was ‘Abuse of Power’ and would respond to the #MeToo movement with productions of The Taming of the Shrew and Measure for Measure. I had to read the information twice to confirm. Yes, they were planning an all-male production of Shrew.

While the Pop-up Globe’s systematic exclusion of female actors had bubbled away since their first season, the invocation of #MeToo in this context resulted in a great deal of hurt and anger. It was the same week that New Zealand’s Women’s Rights Commissioner Jackie Blue told the UN that domestic violence is our country’s leading human rights issue, so to perform The Taming of Shrew, in which a husband psychologically and physically abuses his wife, is inherently political. Nor did it go unnoticed that New Zealand was celebrating the 125th Anniversary of Suffrage. Penny Ashton wrote a brilliant piece for The Spinoff, and the issue received prime time coverage when she appeared on TV3’s The Project to debate Dr Gregory. At this stage, Gregory was not backing down and the uproar continued (this post collected the discourse and arguments). Eventually, Pop-up popped-down and made a commitment to 50/50 gender casting.

Later, during a debate on Australian television, Dr Gregory would win enthusiastic audience applause when he stated that “I think we’ve heard enough from men about #MeToo.”

I went to see the eventual Taming of the Shrew. It was impossible to view it without the doubleness of their original intentions, the knowledge that the standout female actors, lead by Natasha Daniel as Kate, wouldn’t have had the chance to audition for the play. The re-purposing of the play’s framing device had potential: a contemporary Christopher Sly – a bad behaved drunk boyfriend is taken from the groundlings and the company of actors decide to convince him he’s a Lord in the Jacobean era. The final bookend becomes the reformation of the problematic male, when the story of Kate and Petruchio inspires him to pledge to not be so stink to his girlfriend. The irony, of course, is the negative behaviour that he identifies in the play and repudiates recalls the Pop-up’s original gender-based discrimination.

The ball is in Pop-up’s Royal Court to demonstrate an ongoing commitment to inclusivity. Their productions are wildly popular and they are especially adept at winning new generation of Shakespeare fans. They are a major player and leader in Auckland theatre’s ecosystem, and we look to them to continue to evolve.

Similarly, we look to Auckland Theatre Company for leadership. Sadly, the announcement of their 2019 season represents a significant failure of leadership by the company. I wrote about the gender issues in their programming approach for the Waterfront Theatre. ATC’s response to subscriber disquiet about their 2018 season (evaluated later in this review) has created a programming hierarchy in which the company’s mainbill in-house productions at the Waterfront Theatre in 2019 feature all-male writers and all-male directors. Happy 125th Suffrage New Zealand.

ATC’s work in the youth space with the Here & Now Festival (previously Next Big Thing) has consistently shown they can be progressive, inclusive and with it, but this approach has been slow to permeate as a company-wide approach, and 2019 disappointingly signals a giant step back. While they are still transitioning into their role as a commissioning theatre and need to ensure their financial sustainability, ATC are yet to demonstrate a comparable and accountable commitment to intersectional inclusivity in their programming.

I am weary of solely focussing on gender (and reinscribing binaries) or taking an issue by issue approach. The theatre industry’s commitment to inclusion needs to be all encompassing, from who performs to the stages to who has access to see them. I maintain that artists have a duty to lead from the front – this is the responsibility of representation.

The global #MeToo movement does offer an opportunity for the New Zealand industry theatre industry to ensure safety for all practitioners. In my 2017 wrap-up, I wrote that “the response here [to #MeToo] has been muted – does the closeness and smallness of New Zealand’s theatre industry mean practitioners are well-behaved, or just that the bad eggs are well protected?” In January 2018, acting coach Rene Naufahu was sentenced for indecent assault.

In July this year the final week of Auckland Music Theatre’s amateur production of The Wild Party was cancelled. An online petition from a cast member appeared, revealing that this was due to a serious allegation of sexual assault. It stated: “We, as members of the cast, felt that the situation was not handled effectively and therefore we would like to call upon the wider artistic community to support us in creating better processes for managing incidents such as this.” The issue was picked up by NZ Herald and Stuff.

Auckland Music Theatre’s response, posted on their Facebook page, was risible. In a borderline victim-blaming statement, AMT’s Chairperson shrugged off any responsibility: “that several company members from its production of The Wild Party were involved in a late night incident at a bar in Ponsonby last weekend. The alleged incident took place off our premises, and the social event was not arranged by Auckland Music Theatre Inc.” Worse, AMT was not offering any of their own assistance to the affected parties: “Due to the seriousness of the alleged incident, we sincerely hope all the affected parties seek support from the most appropriate agencies.” It was incredibly disappointing that AMT did not engage with the substance of the petition, which called for AMT to support an effort “to create a document that outlines best practice and is held as an industry standard for addressing sexual misconduct, adopted by all artistic organisations.

It is vital that professional and amateur companies transparently adopt best practice policies around sexual and gender based harassment and abuse.

A wider reckoning is perhaps yet to come (if indeed it will). As evidenced by Francis McWhannell’s piece To Name and amend, the theatre and the arts community in general need to make a difficult examination of culpability with patronage.

MUSICAL THEATRE ON LIFE SUPPORT

A truly iconic Kiwi moment occurred on opening night of Shortland Street The Musical when Mark Hadlow turned to the audience to ask “Is there a doctor in the house?” Up leapt Michael Galvin aka Dr Chris Warner (who had been dropped off at the red carpet that night via ambulance) to save the day. Any doubts about the wisdom of adapting New Zealand’s longest running soap into a musical were answered by Auckland Theatre’s Company debut of an excellent production. The masterstroke by creators Guy Langford and Simon Bennett (a directing veteran of the TV show) was to focus on the storylines from the early days of the soap that had been lodged in the nation’s collective memory ever since. The result was an affectionate tribute to the variously beloved/maligned soap, while also giving us a cultural history of who we were in the 90s.

Whether you love or hate either Shortland Street or musicals, the combination is one of the most entertaining and enjoyable theatrical events of the year, and with a five-city tour planned for 2019, there is no doubt the show will soon be world famous in New Zealand, and perhaps further.

The Christmas Cliffhanger was spoiled prematurely, however, when it was announced that the 2019 tour was being cancelled due to poor ticket sales. If even a quality local homegrown show with name recognition couldn’t succeed, what did this portend for New Zealand theatre in general? The NZ Herald and Stuff ran commiseration pieces. The Spinoff’s Sam Brooks concluded his post-mortem: “The show was at 7pm in Auckland – and likely around the country. Do you know what else is on at 7pm? And is free to watch? And if you miss even one night, you’ll have to play catch-up? Shortland Street: Not A Musical.”

The economics of touring can be brutal, and Langford and Bennett were going it alone. Perhaps the show can be resurrected through a more sustainable professional touring and marketing model. If nothing else, the show surely has a long future ahead of it in New Zealand’s amateur societies.

The cancellation of the Shortland Street The Musical tour made for an especially curious juxtaposition with City of 100 Lovers, which was reported to be playing to audiences in the tens at SkyCity Theatre.

City of 100 Lovers was the strangest story in NZ theatre this year. NZ Herald reporter Matt Nippert, who is more often found head deep in Panama papers and tax returns, did an investigative report into the show headlined ‘Auckland musical ‘City of 100 Lovers’ cost $8 million but is playing to near-empty houses‘. The story even made US website Vulture who thought the idea of an extravagant musical playing to empty houses was worthy of a TV series. Seven Sharp then ran a PR puff piece on the show with the producer Jihong Lu taking the reporter out on his Yacht (if it qualifies as “super” is a point of contention). “Here’s a very important question,” asked Jeremy Wells at the top of the piece, “why do musicals get written?”

In the case of 100 Lovers, money was flung at Broadway-adjacent writers and directors to create a Kiwi musical that would appeal to the 4.2 million tourists who visit Auckland each year. The result was less than world-class, the theatrical equivalent of the hop on and off Auckland Explorer Bus. From my review:

There might be potential in the 100 Lovers concept, but it is very clear that the show has been prematurely rushed to production, with the show debuting within one year of the story treatment being commissioned. In New York it is the norm for musicals to spend years in development, and it an ongoing problem here in Auckland that we don’t have that financial luxury. But not investing in development time for 100 Lovers makes the goal of playing indefinitely all the more difficult to achieve, because that relies on enthusiastic audience word of mouth. In committing to a long season, perhaps the creatives will have an opportunity to further hone the show’s dramaturgy.

Unfortunately, in seeking to promote New Zealand culture and creativity to the world, City of 100 Lovers instead ends up reinforcing negative perceptions of our own mediocrity.

If this was Broadway, this show would have opened and closed the next day. At SkyCity Theatre, City of 100 Lovers stubbornly plays on. The 100 Lovers model of a resident show in Auckland is worth trying, but they’ve made it substantially harder for themselves by rushing to put on such a substandard show. If only kiwi creatives had had a crack at the script rather than a New Yorker phoning it in (the music by local composer Tom McLeod is one of the production’s few saving graces).

Still, the good news is that 100 Lovers is providing rare sustained professional employment to a team of local performers and crew. Touring professional musical theatre like Shortland Street The Musical is made more difficult by ‘pro-am’ musical companies which play the big venues and charge the big bucks, but do not pay the majority of their actors. Marketed to look like a professional production, the pro-am model received some much-needed scrutiny by Radio NZ and The Pantograph Punch.

NZ THEATRE MONTH

This was a grassroots celebration and elevation of New Zealand theatre, led by playwright Roger Hall and Malcom Calder, which ran throughout the month of September. I committed to covering the month in Auckland (plus two Wellington shows ). I saw it as an important opportunity to come together as a theatre industry, and argued why the month was important:

Playmarket, New Zealand’s playwright’s agency, recently released an analysis of the programming by our professional theatres in 2017 (producing houses, receiving houses and producing companies funded by Creative NZ under the Tōtara and Kahikatea models).

Playmarket found that companies and audiences love local work: of the 221 staged productions, 79% were New Zealand works.

Playmarket’s breakdown gives a picture of the representation on our stages: 14% were Māori works, 11% were Pasifika, 7% were Asian works, and 48% were works by NZ Women.

Although this data gives only a snapshot of a particular year, the overall trends are notable (while using different data, it can be contrasted to CNZ’s earlier finding that between 2011 and 2015 only 6% of productions by main centre theatres were of Māori or Pasifika work).

What better time then for the inaugural New Zealand Theatre Month?

Sure, it doesn’t look like our professional companies need any encouragement to programme local work – they are committed to telling local stories.

But having a month for theatre provides an opportunity to harness everything that is going on. When companies are focussed on surviving from show to show, there can be little opportunity for telling a national story as an industry.

New Zealand theatre makers produce high quality and truly remarkable work – it is exactly the right time to celebrate this.

While Hall and Calder encouraged the programming of New Zealand theatre over the month (especially by amateur societies), by design the month instigated few events of its own. It was reported that over September there were “650 separate celebrations of NZ theatre across 125 discrete events generated by more than 110 organisations or individuals across the country.”

It was powerful to use their website and see at a glance all the theatre (amateur and professional) happening across the country. It also drew attention to regional absences (does CNZ need to step in to encourage theatre in the West Coast?).

Auckland started strong. Indian Ink and Red Leap Theatre toured return seasons of Mrs Krishnan’s Party and Kororāreka: The Ballad of Maggie Flynn. Bright Star by Stuart Hoar, Orientation by Chye-Ling Huang, Cradle Song by Albert Belz and Uther Dean’s Me and My Sister tell Each Other Everything were notable openings in the first fortnight.

Auckland Music Theatre (a society that is 100 years old) programmed one local work, with NZ Theatre month offering a potential prompt for more home grown musical theatre revivals.

In the final fortnight, The Basement’s A Few Things I’ve Learnt About Dating and Death by Acacia O’Connor had Tim George declaring “the moment actress Acacia O’Connor was screaming at me in German while covered in black war paint and pouring wine into an imaginary glass, I think this might be my favourite show of 2018.” While Retail Therapy’s slick online marketing campaign led to a strong box office, audiences were small at the other Basement shows (even on cheap Wednesday). NZ Theatre Month wasn’t apparently doing much for business at The Basement.

Rendered by Stuart Hoar was given a big budget cinemascope treatment by Auckland Theatre Company at the Waterfront Theatre. Engaging with New Zealand’s entanglement in the war on terrorism, Rand T. Hazou called it a “thoughtful meditation on connections in our globalised neo-liberal world, despite distance and seemingly oppositional constructs.”

While NZ Theatre Month arguably generated some extra publicity for a range of productions nationwide, the challenge will be to go beyond just having theatre people talk to already converted theatre people. The founders envision a five year growth strategy.

NZ Theatre Month was met with a shrug from many people within the theatre community, who didn’t feel that it was for them or relevant to a generation of theatremakers for whom Roger Hall has little currency. Indeed, NZ Theatre Month’s future is rather jeopardised when its instigator writes a factually incorrect letter to the editor commenting on outrage around a high profile murder by whatabouting on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders – an abhorrent conflation.

In 2019 Playmarket will administrate the month. New Zealand Theatre month will only succeed if it belongs to everyone.

OF FRINGE & FESTIVAL

We return to our regular programming by flashing back to the beginning of the year with the offerings from Auckland Fringe and the Auckland Arts Festival.

The great thing about Auckland Fringe, of course, is that there is nothing regular about its programming! Various shows included Force Field from Everyone Cool Lives here, Catherine Delahunty’s up yours to parliamentary life Question Time Blues, and a delightful Roman reenactment experience Caesar’s Rome held in an enthusiast’s backyard (we donned helmets, charged against the barbarians, and drank Mulsum). The Race (the latest from Fringe veterans Hobson Street Theatre Company) demonstrated, as Rand T. Hazou put it, “how theatre can help connect individuals and create a sense of belonging, security and community.” Anders Falstie-Jensen’s Watching Paint Dry, as Nathan Joe dryly stated at the top of his review, was “much more fun than it sounds.” Improv show Mackenzie’s Daughters came with a health warning from reviewer Tim George: “One note for viewers with hay fever and/or allergies: the set is a collection of hay bales, so prepare accordingly. I would have been sneezing but I’d used up all my oxygen from laughing.”

Meanwhile, the Basement Theatre’s challenge to makers for their Studio space was to create a show for one audience member at a time. Siblings Vida and Arlo Gibson both independently made rewarding shows inspired by wombs (Women and Water and A Womb with a View). In Vida’s Water I had the extravagance of lying in a bed while a band accompanied me as I guzzled a glass of water. Arlo’s View took me on a journey through the womb and even played my favourite song as I was birthed into the night. They are experiences I’ll treasure, one of the privileged few able to enjoy them.

There were two judiciary themed works in the Fringe, the artificially sweetened Judge, Jury & Cookie Monster, and the one-night only It’s a Trial! created by Binge Culture and Barbarian Productions. The latter show canvased fascinating issues about how art making is – and could be – financially supported in this country. In my report I noted the symbolic value of having our Prime Minister once again take the Arts portfolio has yet to be matched by meaningful policy action:

But if the Labour led Government did decide to increase investment in the arts, or even restructure how this is delivered, what would they do? It’s a Trial! seized on comments made by Ardern elsewhere that“as long as we [are] constrained by the boundaries of a platform driven by commercial imperatives, we are personally not being as courageous as storytellers as we could be.” The value system implied here is that commerce blunts art, makes makers risk averse, maybe even prevents great art from being made.

Thus, in It’s a Trial!, applicant Ranya Tan-Manning (Anya Tate-Manning) seeks a judicial review questioning the lawfulness of the Government’s new policy to separate the creation of art from commercial imperatives.

Nisha Madhan’s attention grabbing Fuck Rant had Matt Baker saying “Fuck Yeah.” The show was a tour-de-force, the culmination of a line of questioning Madhan had been developing over a number of works. Matt Baker wrote:

With nothing more than some tape, a pen, and a lot of fake blood, Madhan breaks down traditional theatrical concepts of time, body, and space, which allows her to metaphorically address the notion of distance and difference between people. Through a repetitious cycle of decreasing duration, Madhan not only condenses the philosophical weight of these theories to simplistic terms, but consequently makes them more powerful. It’s the kind of commentary on labelling that is resonant to those who understand it, and subtle enough for those who need to hear it, but otherwise wouldn’t, to accept.

First performed as a duo by Julia Croft and Virginia Frankovich, an expanded The Plastic Orgasm, performed by an ensemble of 17, was another must see of the Fringe. Nathan Joe described it thus:

From the show’s first moment, we are confronted by this orgiastic landscape of female bodies, swimming in a sea of clothes. They smash against one another, colliding beautifully and brutally, as if trying to recreate a feminist Hieronymus Bosch. Like punk rock, it’s a battle cry against status quo; like punk rock, it’s also numbing and deafening at times.

The cast enact out fantasies. Not their own fantasies, but the fantasies of the dominant male gaze. Pornographic, excessive and gratuitous fantasies. They enact these fantasies with relish to show how shallow and ridiculous they are. Mayonnaise bukkake, female wresting, the always recognisable Baywatch run. They are loosely choreographed acts of revolt on our android dreams. A wake-up call.

Onto the Auckland Arts Festival, the first programmed by new Artistic Director Jonathan Bielksi. There were a number of international ‘gets’. On the Robert Lepage show I wrote that “18 years from its debut, The Far Side of the Moon is still pushing the frontiers of what theatre can do, the places theatre can take us, and the meanings that we can find.” The stage adaptation of 1984 was an opportunity to assess if we really were having a 1984 moment in post-truth 2018. And for Brigitte Knight, Akram Khan’s Giselle, performed by the English National Ballet, lived up to the hype: “Simply, it is a masterpiece.”

In Jack Charles V The Crown we had the pleasure of being the confidante of an Australian aboriginal acting legend. Tim George, however, found Us/Them, based on the 2004 Beslan school seige, to be a “pretentious trivialisation of a terrible event that strips it of all historical, political and cultural context.”

The local programming was led by Hone Kouka’s Bless the Child, which dealt with themes of child abuse. Sharu Delilkan and Tim Booth responded:

We won’t forget this play and we hope it won’t just ‘facilitate discussion’. Our earnest hope is that there’s societal change around the corner and that this play’s essence will become ‘obsolete’: as an intriguing and tragic milestone of the past, a passage of NZ history that never should have happened. A pivotal point for the senseless suffering of those most cherished, dear and vulnerable.

The Naked Samoans made a much anticipated reunion in The Naked Samoans do Magic, but something was off about the show – the troupe’s style curtailed by the emphasis on pulling off feats of illusion (Sharu and Tim missed their “profound and bitchy honesty” the most). The show did end with an amazingly resonant magic trick – the sudden appearance of a cohort of PIPA students (whose school had sadly closed at the end of 2017), a gesture proclaiming the future of Pasifika performance to be in good hands.

Nathan Joe found that in Auckland Theatre Company’s Still Life with Chickens by D.F. Mamea (in which Goretti Chadwick co-starred alongside a chicken puppet), “every beat and moment [was] fully realised to create a warm tale of friendship and loneliness.”

Silo Theatre co-produced Body Double by Eleanor Bishop, Julia Croft and Karin McCraken, who assembled the show as a response to the various narratives that shape and define women’s relationship to desire in their lives. Rachael Longshaw-Park unpacked the show’s representation:

It’s clear that the material of the show is overtly heteronormative, white-centric, middle-class and focuses on the cis experiences of sex and desire. Perhaps this is because the show directly responds to popular culture that has been single-handedly dominated by the one-track white/cis desire narrative for so long. It also pays to note that the creators are also white/cis women. Either way, the content of the show may only feel accessible for those who fit within that cross section. Surprisingly, despite the incredibly self-aware commentary between the performers and the audience that holds the vignettes together, this isn’t addressed, which feels unusual when the opportunity to speak directly to an audience about the construction of the show and its content is already set up as a convention and utilised.

Ahi Karunaharan’s sold-out season of Tea was an Auckland Arts Festival triumph, an “intimate epic […] taking us into the crevices of Sri Lankin history.” The Arts Festival plays an essential role when it is able to support local work with large casts that might otherwise struggle to be programmed elsewhere. Nathan Joe concluded:

The stories within this epic give a broad sweep of a nation in crisis. This is a world recovering from change. The world, as we know, is constantly changing, so it’s immediately resonant, but Karunaharan loads it with a specificity and knowledge of the period and culture so that we are confronted with a remarkably clear period piece (or pieces) as well as social commentary. The backdrop of colonialism and civil war is impeccably tackled, not as a dialectic, but as a fact.

It’s daring to write such a big play, especially in a theatre ecology that doesn’t always reward such risks. Here, the investment has paid off and we’re left with a game-changer for bigger and braver plays. Ambitious with a capital A.

THE ESTABLISHMENT

Auckland Theatre Company had an uneven year as they continued to experiment with how to use the ASB Waterfront Space – and ended up testing the tolerance of their subscriber’s tastes.

In Pip Hall’s adaptation of Maurice Gee’s 1979 novel Under the Mountain, director Sara Brodie took up the challenge of how to theatricalise red-headed twins Rachel and Theo’s battles with the evil Wilberfi. Sharu Delikan and Tim Booth reported that “they had some of us physically jumping out of our seat at times, like one would expect in a perfectly believably frightening horror movie or thriller.”

While the 1960s East London set Filthy Business by Ryan Craig was let down by the writing, it was a production otherwise emjoyed by Camilla Walker. In reviewing ATC’s Youth Here & Now Festival, I summarised: “The best testament for all three shows is you wish they had more stage time – for Tender to be able to explore more deeply, for You First to build its world more completely, and for Alice – well, I could have sat in this storytelling wonderland for a long time.”

The two shows that proved troublesome for the company were NZ relocations of plays by canonical playwrights George Bernard Shaw and Anton Chekhov.

Excitingly, director Eleanor Bishop made her mainbill debut with her intervention into Shaw’s controversial 1893 play, Mrs Warren’s Profession. Sharu Delilkan and Tim Booth found the play to be timely:

It attempts to expand on Shaw’s prescient commentary on feminism, exploitation and the plight or power of sex workers. However, the lack of conviction with which these edicts are delivered diminish these messages. Ultimately the effect is repetitive, rather than evoking empathy and understanding.

Theatre Scenes offers the ability for readers to post comments to our reviews, but rarely are they compelled to. Mrs Warren’s was different. A selection of comments gives an impression of the backlash towards the production:

“I saw this on Tuesday and became one of the empty seats after interval. ATC seems to be making a habit of the disconnection you comment on, and it’s a shame; I’ve yet to enjoy any of the plays from this season.”

“To rework S[h]aw’s words showed ignorance in the face of such a talented writer and to set it now in a kitch kiwi land assumes the audience is stupid and unable to understand the relevance of this timeless play’s meaning.”

“I could leave my seat empty except that I was sitting in the middle. I have never been to such a poorly adapted play.”

“Too many vulgar sex acts – that detracted from the Main message. Just Awful.”

There were similar objections to the NZification of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, which had been rewritten by Albert Belz, Tainui Tukiwaho, Philippa Campbell and director Colin McColl. My assessment was this was largely successful, finding parallels between the original Russian context and attitudes to land between Te Ao Māori and Te Ao Pākehā. Camilla Walker wrote “this is a show full of the complexity and agility, comedy, tragedy, and dark irony that are the hallmarks of the original.” Readers disagreed in the comments: “We stayed for the whole thing but we really both felt ripped off because it had been advertised as “The Cherry Orchard” by Anton Chekhov and we had been looking forward to it, as we had seen this play many years ago. Huge disappointment – if Mr Chekhov had been invited to view this version I suspect he would be suing the pants of you!”

New Zealand relocations/reworkings of classic texts has been a common tactic (with Eli Kent and Emily Perkins tackling Ibsen for ATC in recent years), so the heated objections to messing with the classic plays in the 2018 season are curious (does it have something to do with the gender and cultural politics explored in the adaptations?). As previously noted, ATC have responded with a highly conservative and narrow programme of plays for the Waterfront in 2019.

Silo Theare, headed by Artistic Director Sophie Roberts, are leading the way in making progressive programming choices in touch with our contemporary landscape and conversations. Even so, it is apparent how much they are constrained with what risks they can take, producing only a small number of shows each year.

The Body Double co-production was followed by a return season of Cell Fish by Miriama McDowell, Rob Mokaraka & Jason Te Kare, which was a late switch in their announced programme. Unfortunately, as Matt Baker reported, it had still to surmount the fatal flaws evident in the work’s 2017 Arts Festival debut.

As Nathan Joe wrote, Hir by Taylor Mac (featuring a powerhouse performance from Rima Te Wiata) was “a play for today, perfectly capturing the zeitgeist and reflecting the current paradigm shift in our still-evolving identity politics.” Putting a gender blowtorch to the masculine American canon of plays like Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, it was “a blistering portrait of the nuclear family blown to pieces.”

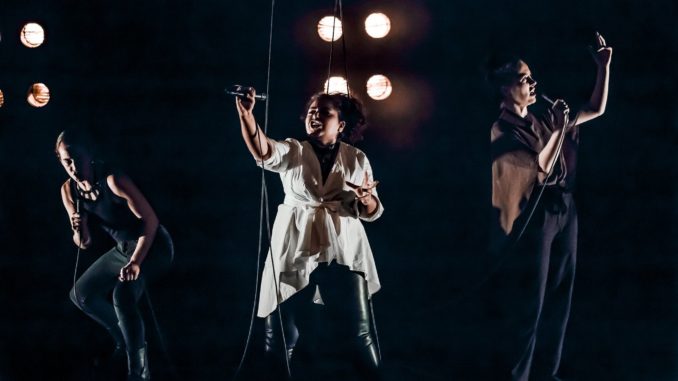

Tim George welcomed the overdue return of Joel Tobeck to the stage in Q Theatre highlight Mr Burns, “who dominates the play’s third act as a bastardised amalgamation of the title character, Kelsey Grammer’s Sideshow Bob and a Captain Planet-level metaphor for the nuclear fallout blighting this future USA.”

Here Lies Love made for a disappointing finish for Silo’s year. Rather than the stage musical, Silo opted for a concert presentation of David Bryne and Fat Boy Slim’s disco album inspired by the life of Imelda Marcos. Jennifer Ward-Lealand’s ability to interpret the story of her songs was unmatched, but context and interpretation was otherwise missing from the presentation. Sharu Delilkan reflected:

If you’re happy to dance your cares away in a vacuum Here Lies Love is definitely for you. But if you’re interested in being educated about Imelda Marcos and her effect on the Philippines then you may end up disappointed like me. […] in a city where Filipinos represent the fourth largest growing Asian community, it is strange that this production doesn’t demonstrate much consultation with the rich and vibrant Filipino community in NZ.

BASEMENT BIRTHDAY

The Basement kicked off a huge year with a packed opening event curated by FAFSWAG and ended with a celebration of their 10th birthday (a “decade of disruption”). It’s been an impressive trajectory for the theatre over the past ten years, directed by a proactive and caring response to the needs of artists and where art forms are heading. ‘Theatre’ is a wholly inadequate umbrella term for the multidisciplinary events that the venue hosts. Choreographer Tallulah Holly-Massey was the 2018 Basement artist in residence (Cynthia Lam reviewed her shows Mammoth and Bad Mood).

The Basement has recently made a superb commitment to Matariki programming. 2018 included Te Waka Huia and Upu Mai Whetū, a glorious night of Māori and Pacific poetry interpreted by a top lineup of actors. Gabriel Faatau’uu-Satiu described the latter as providing “a pathway towards our Māori and Pacific literature pioneers who have paved a way for our stories in the past, retold and relived in the present, so that we can collectively work together on how our stories progress forward in the future.”

Jess Holly Bates found recognition to be at the core of writer/director Mya Morrison-Middleton’s Maumahara Girlie:

It acts as an invitation to clear space in this neocolonial timewarp we seem jammed in. In this way, Maumahara Girlie is both a hopeful encounter and a question mark. This work must be unpacked again, and I hope this happens in its future life. It peels back pain and disconnect with delicacy, and leaves its audience chewing on uncertainty. It’s a meditation that is not supposed to satisfy you. And that feels every bit as slippery as it should.

The Basement Tapes by Jane Yonge and Stella Reid and The Basement Theatre made for the perfect partnership. Rachael Longshaw-Park welcome the change of pace of the show:

It’s not uncommon for work that is performed at theatres such as BATS or The Basement to be politically and socially charged, especially in the current political climate, so it’s a change of pace to see a piece of theatre that doesn’t claim to be anything more than it is – a solid piece of storytelling. The Basement Tapes strikes a fine balance of suspenseful narrative, comedy and clever timing. At its core, this play is a ghost story – regardless of whether you believe the ghost in question is real or the granddaughter is simply losing her mind.

The Basement Tapes would go on to win a Fringe First Award at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe (as did Last Tape’s Valerie). An outstanding achievement, but it also speaks to the quality of the work performed at The Basement that the show was not a sole standout of the year.

Camilla Walker named Ana Chaya Scotney’s portrayal of six rangatahi from Te Matau a Māui, Hawke’s Bay in The Contours of Heaven as “one of the best performances I have ever seen.”

Cult Show: The Revitalization of the New Zealand Women’s Archive, featuring the team of Saraid Cameron, Amelia Reynolds, director Nisha Madhan, and dramaturg Kate Prior, made an essential theatrical contribution to feminist discourse. Here’s Rachael Longshaw-Park:

Often when people anticipate feminist theatre there is a common perception that you will leave the theatre feeling guilty; politically charged theatre has deep roots in anger and frustration that often can be directed at the audience. Cult Show takes a slightly different approach that prevents it from coming across as preachy or dogmatic; the narrative cleverly plays out the anger at the root of the problems through the personal conflict between Cameron and Reynolds. The audience get to be a fly on the wall during the grittiest moments in the show, allowing for reflection rather than aggressive interrogation of a live audience.

Victoria Abbott hat-tipped a number of practitioners with Run Rabbit; Nathan Joe found so many things to unpack and praise in the show. On his Facebook page, Matt Baker called it one of the best pieces of theatre he’s ever witnessed.

Other Basement highlights through the year included Amber Liberté’s direction of Pool (No Water) by Mark Ravenhill, Agaram Productions’ First World Problems, and return seasons of I Ain’t Mad at Cha and Your Heart Looks Like a Vagina.

Nathan Joe found the Auckland season of WEiRdo from Waylon Edwards, William Duignan and Jane Yonge timely, “coming at the tail end of Taika Waititi’s recent comments that New Zealand is “racist as fuck.”

To close the year, Wellington’s Red Scare Theatre Company visited with Movers, and Rose Matafeo and Alice Snedden savaged the workplace Xmas party with Work Do.

MOVING TE POU

While committing to supporting emerging artists, The Basement has long since passed the point where it can provide space to all comers. Te Pou Theatre has filled the gap with its Rangtahi Festival, providing a platform for new writers and creative teams guided by tikanga Māori. Rangatahi shows for 2018 included Herstory, Beneath Skin and Bone, Dope and Tampocalypse.

Te Pou also hosted the most fascinating theatrical event of the year: a season of Eugène Ionesco’s The Chairs interpreted through four different cultural frames: The Chairs Pākehā season, He Tūru Māu Te Reo Māori Season, O Nofoa Sāmoan Season and 等凳 Cantonese Season. Camilla Walker reviewed all four seasons and it a delight to read her experience and discoveries as she engaged with the adaptations (as are Gabriel Faatau’uu-Satiu’s and Nathan Joe’s contributions).

While Te Pou is one of Auckland’s most welcoming theatres, the sound bleed from the neighbouring basketball court also makes it one of the most frustrating. The Chairs seasons was the last in the space, with a new theatre being built at Corban Estate for 2019.

MENTAL HEALTH

An undeniable trend in 2018 was the amount of work that engaged with mental health, playing as a backdrop to the Government’s Mental Health Inquiry: Such Stuff as Dreams, Near Death Experience, Breathe, A Lost Cause.

Contextualizing the Edinburgh Fringe fundraising season of Last Tape’s Valerie at Q Theatre, Matt Baker wrote:

Mental health in New Zealand is a prevalent issue and, by consequence, necessary to discuss. 16% of New Zealanders are diagnosed with a mental health issue in their lifetime, comorbidity increases the risk of death, and our suicide rate is the second highest in the OECD. Mental health is also prevalent in the arts, especially theatre, with a 48% diagnostic rate. The advantage to this, however, is that theatre contextualizes its content with people. The what becomes a who, and the who provides us with an empathetic link that resonates beyond mere statistics and has the possibility of reaching more people.

During their time playing the Edinburgh Fringe, Last Tapes put into practice their own mental wellness plan. Creator Robin Kelly told The List:

Positive self-care in the Fringe has been a lynchpin of our strategy for coming to Edinburgh. We’re coming from New Zealand, which means a huge financial burden, but leaving our support structures behind. So as a company we’re looking inward to support each other with super-practical steps. The most important of these is that we have scheduled time across August to check back in with families/therapists/partners/friends at home, and we all understand that that is a priority which supersedes anything else.

Valerie sensitively engages with mental health issues, and it is brilliant to see the company actively taking steps to support wellbeing off the stage.

Sometimes theatre’s representations of the real can profoundly affect an audience. Catherine Hart for The Pantograph Punch asked how we are using trigger warnings in NZ.

The representation of suicide ideation in Natalie Medlock’s Near Death Experience made for a harrowing watch. Nathan Joe wrote that while it was a difficult play to recommend, “those looking to explore the darkside of mental illness aren’t likely to find a more relentless portrayal than in Tito’s Tabby.”

The onus is on makers and programmers to ensure that proper care and responsibility is taken when exploring mental health on stage. It is not always clear that this happening, or whether productions with a kaupapa of increasing awareness of mental health issues would find endorsement from the Mental Health Foundation. It is an area we need to be mindful of. George Fenwick wrote a great piece for the NZ Herald on what is being done to safeguard mental health in the arts.

THE AGITATORS

Auckland has developed a rising cohort of independent theatre artists making smart and socially aware work. Let’s call them the agitators.

Sam Brooks cemented himself in the top echelons of New Zealand playwriting with his trifecta of Twenty Eight Millimetres for Auckland Pride, Burn Her for Q Matchbox, and Jacinda for the Actors’ Program. In reviewing Jacinda (Brooks’ Angels in America treatment of the 2017 election), Nathan Joe commented:

It’s a privilege to witness a playwright flex his muscles in an interesting and new direction with the likes of Burn Her and Jacinda. And, while the former’s taut and tense storytelling is reminiscent of a high-quality television drama made with enviable craft, Jacinda is, for my money, the more resonant and ambitious piece. Full of wisdom, humour and heart.

Proudly Asian Theatre, as Matt Baker put it, “represents an integral component to both our theatrical and cultural landscape.” In Auckland this year they’ve held playreading events and produced Roots for Auckland Fringe and Orientation by Chye-Ling Huang, which deservedly won the 2018 Auckland Theatre Awards Hackman Theatre cup for most original production. Rand T. Hazou wrote:

Orientation is smart and skilful art produced by a talented cast of bi-cultural and diasporic Asian artists. Each of these artists has probably experienced the pressure to adapt and ‘assimilate’ so as not to feel like an outsider. The problem is, the binaries of power that exist in Aotearoa – which are a legacy of colonialism – continue to mark those who are racially different as ‘the other’ and limit their contributions. It is for this reason that this play and the work of these artists and the company are so important. If love can transcend race than we need more work by these talented artists to show us how.

Then there was Medusa, created by the powerhouse team of with dramaturgy by Kate Prior. Featuring 200kgs of clay and at least twice as much rage, it laid waste to patriarchal and theatrical convention. For Cynthia Lam it smashed all “preconceptions of what theatre and the mythological story of Medusa are about” and was a “an aural, visceral and mind-blowing ‘out-of-this-world’ theatrical experience.”

Zanetti Productions‘ Lydia Zanetti and Helen Sheehan are my final agitators to profile. They are the producers behind the Auckland Fringe and some of the most essential theatrical work in New Zealand (Medusa, The Contours of Heaven, Run Rabbit, Body Double, The Plastic Orgasm…). Zanetti Productions are thoughtful curators, supporting must-see work that pulses with life and purpose.

EVEN MORE

- Binge Culture’s Yorick! provided the lingering earworm of the year with their closing tune: “I don’t want to die today, I don’t want to die…”

- Highlights of Auckland Pride included Night of the Queer, Fala Muncher and Gays in Space (a show which included “a sentient sex robot, death, illness, heartbreak, intergalactic Grindr hook-ups and lots of Chris Parker shouting.”)

- Speaking of Chris Parker, he followed up Comedy Festival Triumph Camp Binch with the ultimate act of brotherly devotion: introducing his sister Liv to the industry in Sibs.

- Leon Wadham’s Giddy was another Comedy Festival breakthrough, “like a hot knife in butter” according to Nathan Joe.

- Massive Company premiered Sightings, but somewhat lost its bearings.

- Indian Ink debuted new show Welcome to the Murder House in Wellington, which will come to Auckland in 2019.

- Prayas’ Dara was an epic encounter with Mughal history.

- The University of Auckland’s Summer Shakespeare couldn’t survive against the Pop-up Globe and cancelled their Summer production (the already cast all-female Two Gentlemen of Verona production continued without support in a streamlined Auckland Fringe production). The Summer Shakespeare Trust trialed an new entirely Summerless and Shakespeareless model by touring Michael Hurst’s scintillating production of The Changeling across various venues in Winter.

- Black Grace made a visionary move in opening up the ASB Waterfront Theatre for a free performance weekend of The Guerilla Collection. Imagining what a Pacific-led Tāmaki Makarau will be like in 30 years, theatre artists Leki Jackson-Bourke, Paul Fagamalo, Bella Kalolo, Victor Rodger, Vela Manusaute and Anapela Polataivo collaborated with Black Grade dancers (Rodger created a brilliantly caustic tale of a Pacific reclamation of Ponsonby).

- Barbarian Productions’ Soft N Hard provided a gender-dividing Tempo Dance Festival highlight.

- STOMP returned to New Zealand to make some noise.

FINALLY,

I’ve gone through a number of emotions as I’ve revisited the year in Auckland theatre: frustration, exhaustion, but also delight and joy, especially reading back the contributions from our generous team of reviewers that helps bring these shows back to life.

I am now a Wellingtonian, having moved at the end of November to take up a dream position as a Lecturer in Victoria University’s Theatre Programme. I will continue my mission as Theatre Scenes editor from my new base.

This year I have heavily felt the responsibility of covering theatre in Auckland after a number of platforms had exited the market. I am grateful for everyone who has contributed to Theatre Scenes this year: Sharu Delilkan, Tim Booth, Matt Baker, Nathan Joe, Brigitte Knight, Tim George, Rachael Longshaw-Park, Camilla Walker, Cynthia Lam, Rand T. Hazou, Gabriel Faatau’uu-Satiu, Maulik Thakkar, Jess Holly Bates, Jonty Crane. We are all volunteers, sustained by our love of theatre and belief that it is worth talking about.

Our commitment to Auckland continues in 2019, and I look forward to contributing commentary from Wellington.

SEE ALSO:

– The Pantograph Punch: Whakanuia: Ten Things to Celebrate in New Zealand Theatre in 2018

– The Theatre Tourist: Top 5 of 2018 (this travelling reviewer spent most of their 2018 in Auckland!)

Theatre Scenes Theatrical Year in Reviews: 2017; 2016 ; 2015 ; 2014 ; 2013 ; 2012 ; 2011 ; 2010

Leave a Reply