Identity Quest [by Sharu Delilkan and Tim Booth]

What does Afakasi mean? The urban dictionary definition is “used by Samoans to classify those who have one Samoan parent and one Palagi parent. Originates from the word ‘half-caste’.” The Samoan Observer provides a great commentary which ultimately concludes that: Afakasi is “to experience TWICE the world around us”. I love this perspective, although that is all hypothetical as we find out when watching Antonia Stehlin’s original work Afakasi. Unlike some perceptions that life is a bed of roses if you’re of mixed race, in this case it’s revealed that it is certainly not one of privilege, confidence, fun, versatility and uniqueness. Stehlin tells us that that life as an Afakasi is riddled with confusion, self-doubt, ostracism, and above all a feeling of disconnect from both worlds you’re technically a part of.

Having seen Afakasi, originally titled Halfatasi, in its development incarnation on stage as part of Red Leap Theatre’s INCUBATOR workshop series in 2013, this show has never really left my mind.

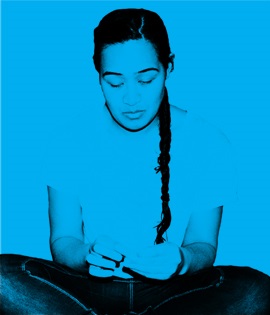

It is great that the promise and intelligence of the initial concept is finally being realised as a full theatre production at the opening night tonight starring Katie Burson (Co-Physical Theatre and Endangered Panda) and Antonia Stehlin (writer and actor). The two very competent actors astutely represent the split personality of Leilani Etuale through the voices, singing and musicality of the Henderson Choir EFSNS – Savili Itamua, Siatuolo Alexandra Mareko, Gloria Leinati Nepo, Hope Stehlin-Mareko, Elijah Tuuga-Stevenson, Christopher Tuuga-Stevenson, To’ali’i Peteru – and percussionists – Andrew Lalofau Tagaloa and Neville Niulesa – from Stehlin’s church, HENDERSON EFSNS (Christian Church of Samoa in New Zealand).

Both of us loved the presentation of this story, where ‘Leilani’ expressively utilises both Samoan and contemporary movement, song, music and spoken word, to drive and prove to all and importantly to herself that she is not one or the other. And as with anything in life she is inevitably confronted with this truth.

Using music and movement to tell this story without actual theatrical dialogue, but more spoken word, is very powerful in this instance. I particularly enjoyed the way in which mime is used to great effect. Unlike many contemporary dance pieces, Afakasi’s movement is deft and almost definite rather than leaving much to audience interpretation – something I think works particularly well. And because of the clarity of the mime and movement we are rarely left in the dark about what’s being displayed on stage – the clarity of movement is poetic yet slick.

But that being said although Stehlin technically straddles both worlds, without feeling an integral part of either, her version of herself in Afakasi is definitely one that gives us a little bit more insight into the Samoan culture. This is evident by her use of a Samoan White Sunday choir, instruments, outfits and language. Less insight into her Pakeha side is expressed, something that the piece might benefit from if the idea is to give a balanced opinion. But since this is meant to be autobiographical it is understandable that she may wish to embrace her Samoan culture more than her Pakeha roots.

The 40-minute piece is dense with heaps of movement and activity taking place throughout. I like the way no words and or movements are wasted and that as audience members we are given the essence of her thoughts and journey rather than an interminable life-story version which we are often subjected to with new works on stage. A particular favourite is the time-lapsed almost ‘Harold Lloyd-esque’ sequence where the backstory is told within a couple of minutes at the start of the piece at ‘fastforward’ double pace.

The fantastic and highly energetic (occasionally violent) performances morph through a plethora of social issues including identity, acceptance, abandonment, conflict, culture, belonging, joy and humour as well as tragedy.

The four-part harmony from 7-piece the choir as well as the accompanying duo of musicians on stage was a great device used to lull us into a false sense of security prior to the choppy waters that lay ahead for the lead characters. The use of the traditional fala (rolled up mat) heightens the drama with its sparing but effective interjections into the overall narrative.

It was a pleasure to hear Samoan spoken alongside, over, around, and more often than not instead of English – which expressed and traversed stark conflict through sarcasm to hilarity as the question of what it means to be Samoan was richly debated but thankfully not necessarily fully resolved. The exclamations of spoken word of the chorus members grounded the piece for me – representing values, judgement, morals, conscience, culture and humanity, and formed a nice counterpoint to the at times stark yet frenetic humour of the performers in the foreground.

Afakasi is definitely worth a look in, whether you know the subject matter or not. It’s a memorable truly Samoan show which manages to avoid the trap of stereotyping cultures, exuberantly presented by multi-talented performers.

Afakasi plays at The Basement until 31 October. Details see The Basement

Leave a Reply