Ready! [by James Wenley]

When I teach A Midsummer Night’s Dream to first year uni students I test their knowledge of the play in a quiz where, divided into four teams (Lovers, Nobles, Fairies, Mechanicals), they compete to win a block of Cadbury Dream chocolate (of course). When I ask them to name a fairy other than Puck, Oberon, and Titania, the students struggle. If you’re an actor auditioning for Midsummer, you probably wouldn’t have your eye on one of these fairies – the mechanicals are much more exciting (unless the Director has a wicked concept for them, like Michael Hurst’s senior citizen chorus at the beginning of the year). When you have drugged lovers, warring fairy royalty, and a Bottom with an ass for a head, the fairies Peaseblossom, Mustardseed, Cobweb and Mote don’t get much of a look in.

Peaseblossom has only four lines in the play – “Ready”, “Hail Mortal”, “Peaseblossom” and “Ready” again. That’s not a lot to go on for someone playing this character, let alone creating a solo show around them. Nevertheless, Tim Crouch makes a compelling case for Midsummer being the fever dream of one Peaseblossom the fairy.

Crouch’s work is invested in the ways live drama can uniquely tell a story with an audience. He’s made a series of solo works about minor characters in Shakespeare – Caliban, Banquo, Malvolio, Cinna the Poet – part of a philosophy about making work for young audiences were the minor characters can be cast as heroes. He’s also known for An Arm, An Oak Tree, and The Author. After five years of asking, the British Council have finally coaxed Crouch over to perform in New Zealand for the first time.

At the end of Midsummer Oberon says they will bless Theseus’s house, and as we enter the Musgrove Studio this is the task that Crouch as Peaseblossom is almost too diligently performing, commenting on everything he sees – clothing, cellphone covers, he notices my notebook and blesses me for sitting critically for an hour and writing “intelligent, pompous things”. Flowers and odds and ends – remnants of a wedding celebration are scattered on the floor. A chalkboard to one side announces “Peaseblossom’s Dream”. On the other side Crouch’s son, Owen sits coolly at a desk with a script and laptop in front of him to play composer Karl James’ suitably magical music. Umbrellas and a blow-up sun are attached to the rig overhead. There’s a disco ball too, which is later used to make patterns above us. It’s like the lighting design has been chosen by a committee of children, selecting the prettiest coloured gels.

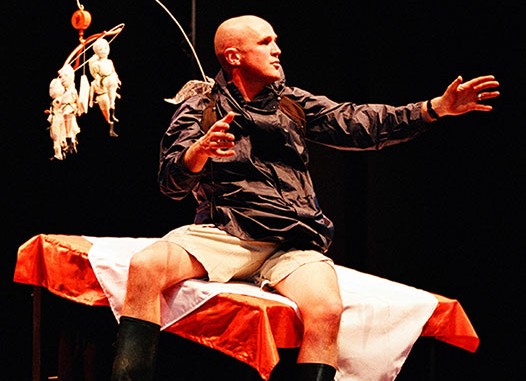

Crouch wears a dark navy raincoat, shorts, wonderful pink Wellingtons, and teeny tiny plastic wings on his back. His Peaseblossom is a gentle soul, who narrates the show with an easy humour, commenting both on the story, and the way the story is being told. His light vocal register weaves a palpable spell and draws us in.

The play is structured into six dreams in which the plot of Midsummer is refracted through the perspective of our fairy-narrator. There are some wonderful Jungian moments, including a fear of performing naked and teeth falling out. Peaseblossom is astounded by the triple wedding and the weirdness of the adult world. They look on in horror as love juice is poured onto the eyes of its victims. Hermia’s Dad is called out for wanting to put his daughter to death. Theseus’s wooing of Hippolyta with his sword is called into question. They wonder why everyone claps at the end of the play-within-the-play after Pyramus and Thisbe have killed themselves. I’ve long been fascinated with the darkness inside the Midsummer comedy, and while Peaseblossom’s dreams don’t quite tip into nightmare territory, it does capture the complexity inherent in the original text. Peaseblossom as observer sees love as driven by jealousy, power, control, punishment. If this is love, they do not want it.

I reckon audiences seeing I, Peaseblossom would nail my Midsummer quiz and win the Cadbury Dream. Shakespeare’s narrative is retold with clarity, with a liberal sprinkling of the original text. But there’s more to the work than just a retelling. Crouch teases out questions of why we continue to perform this story in particular, and why we go to the theatre to dream in general.

In one of their dreams, Peaseblossom encounters the love-in-idleness flower. Peaseblossom says the magic only has power if you are asleep. But if theatre is a dream, then he must be asleep and susceptible to its power. But if he is dreaming, then the flower isn’t real. Like Shakespeare’s play with its invisible fairies and good-bad acting, Crouch is interested in the power of the audience’s imagination to transmute what they see in front of them.

Crouch talks of the audience being co-authors of this work. He enlists collaborators to play the lover characters from their seats and has them read out lines or perform simple tasks (go to sleep, but don’t really go to sleep). A teddy bear stands in for the Changeling boy at the centre of Oberon and Titania’s disagreement. Crouch climbs precariously through the Musgrove seating block and declares an audience member to be a thistle. We are in a space of play, where anything can stand in for the other.

This is a space that is threatened when an audience member, when asked for their name, declares “I’m not playing”. In this resistance the real returned. Peaseblossom’s mask of vulnerability was lifted to reveal the vulnerability of Tim Crouch, performer, battling to return to the make believe. Crouch navigated us back with sensitivity and grace.

This was a brief moment of tension, but there was another tension that lingered over the work: the knowledge that we weren’t the ideal audience. The target audience is for eight-year olds (not that you would know from the marketing). This shouldn’t matter – it’s a charming work that does not talk down to its audience, no matter what age. You can see how the work can fluidly adapt to whoever is front of Crouch, including our “metropolitan” audience on opening night. But references that we weren’t children seemed out of keeping with the spirit of it all – better to say we were children, and allow us to pretend. This is a show that should appeal to the sophisticated inner child in all of us.

I, Peaseblossom is presented by the British Council and plays at the Musgrove Studio until 12 December. Details see The Maidment.

SEE ALSO: Theatreview.org.nz review by Dione Joseph & Metro review by Simon Wilson

Leave a Reply