[The Rebirth of the Theatre]

Of the many great responses from liberal tweeters commenting on the backlash to Jodie Whittaker’s casting as the thirteenth Doctor, my favourite was from playwright Dan Rebellato:

EXT. PLAYHOUSE. 1660.

AUDIENCE MEMBER runs from theatre.

PASSER-BY: What ails you sir?

MEMBER: ’Sblood, they have a WOMAN playing DESDEMONA.— Dan Rebellato (@DanRebellato) July 16, 2017

That woman is believed to be Anne Marshall, who played Desdemona in the first English production to feature professional female actors on 8 December 1660. The playhouses had reopened for the first time in 18 years following the end of puritan government and the restoration of King Charles II earlier that year. (That would be like shutting down cinemas and Netflix for two decades… Imagine what that must have been like after such a long absence!). The public flocked back, but it wasn’t quite like it had been before. Charles bought new tastes from his time spent in French exile, including… women playing women.

In Nell Gwynn we see the very sort of scene described in Rebellato’s tweet. A woman on the stage? The death of the theatre splutters Edward Kynaston, a self-important actor specialising in female impersonation. Played with wonderfully anxious bile by Byron Coll, he mansplains why women should not be take his roles, that theatre is a place of artifice, and with a final haughty flourish, that no woman can play a woman as well as he can.

Nell Gwynn followed Marshall in 1666. Playwright Jessica Swale condenses the timeline for the play so Gwynn appears on stage at the start of this new movement. We see her rise from a playhouse orange hawker, to a box office draw, to catching the eye of the King and becoming his mistress. Thus, she was the preeminent celebrity and sex symbol of the English restoration period. Gwynn, played by Claire Chitham, slyly remarks that if she dared to attend an event in a dress she’s already worn in public then the pamphleteers would have a field-day.

So, one of the more self-evident talking points with this play is how much of a modern woman Nell Gwynn is, and how contemporaneous their entertainment era is with ours.

For us, as female gaze and intersectional storytelling grows as both an ethical and commercial force (this is where I name-check the likes of Wonder Woman, The Handmaid’s Tale, Orange is the New Black…), monolithic narrative walls are crumbling.

For the restoration, the revolutionary act of putting a woman on the stage changes everything. While it is immediately a box office smash, Gwynn’s company realise that you can write for any woman you want… real women. New narrative possibilities are opened. (The qualification is that in the actual historical period bawdy, bosoms and double entendre were largely the entertainment drawcards.)

These modern links are conveyed rather obviously in the production’s costuming, with flashes of ripped jeans, floral boots, and pink booty shorts underneath the sumptuous period attire. Elizabeth Whiting’s costumes would be the talk of the town if they appeared as a Restoration chic catwalk collection, but in this context do not follow the contemporary/period mash logic far enough to make a coherent artistic statement beyond the immediate visual pleasure.

A second talking point is how Swale is using Gwynn to decentre expected narratives. Swale originally wrote the play for the London Globe stage (premiering in 2015), which usually features plays about great Kings and great men. In other hands, Gwynn might have been the sexy temptress that cameos in a play entitled Charles II. In this case, though Tim Balme’s portrait hangs above the proscenium, Balme’s Charles is the bit-player in Gwynn’s narrative. (McColl resists the obvious symbolism in switching it to Chitham’s portrait by the play’s end.)

The challenge with Gwynn is the star-power the role requires – she needs to appear as a breath of fresh air in the onstage scenes, and a force of wit and chumpah offstage. Chitham pulls both off with exuberance. She runs rings around the other stage players, rejects King Charles’ rote pick-up attempts, and fiercely stares down the elites who see her lowly status as a mistress too far, strengthening her resolve to have her stage and her King too.

But for all her independence, public acclaim, and social climbing, the character is faced with the contradictions of her rise: the need to work hard to maintain her favour with the King and see off rivals; the disapproval from her family; her Kardashian-like sex symbol status and the resulting anxiety that the public come to gawk at her because of who she sleeps with, rather than her own talent; and the need for reinvention – she considers going nude in the part of Lady Godiva to remain relevant.

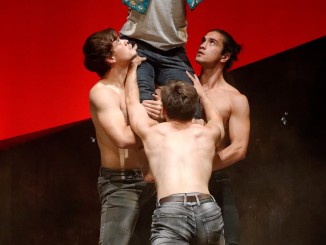

The rest of the cast are extremely well-stacked: Tim Balme – who makes a welcome reappearance to the stage as the playboy King – a sensitive, sometimes-feminist Charles trying to keep his head so he doesn’t lose his head like his father; Andrew Grainger, a boisterous match as the leading man Charles Hart, who first takes Gwynn through acting 101; Mark Hadlow, brilliant as the fumbling playwright John Dryden and a slimy royal adviser; Hera Dunleavy, the ever-realist costume lady; Roy Ward, the put upon company leader; sprightly newcomers Samuel Austin and Vida Gibson; musician Charmain Keay; the aforementioned Coll; and Alison Bruce has a run of outrageous costumes and characters.

Under the direction of Colin McColl the company take to this love-letter to the theatre with enthusiasm, relishing every opportunity to tear down the fourth-wall – from the preshow where they sell oranges to the audience, to the musical interludes arranged by John Gibson using ditties from the era. The music, together with the snatches of performance text, are a tantalising taste of a time period – rediscovering and expanding its artistic expression – that we almost never get to see on our contemporary stages.

As this was written for the Globe, scenically the play doesn’t need much. ATC, however, have indulged – and can you blame them? Rachael Walker continues the streak of breathtaking designs seen over the Waterfront theatre’s first year, taking us effortlessly from the playhouse to palace (it must be rather liberating for ATC to be able to utilise beautiful scenic drops with the theatre’s fly pulley system). The scenery and costumes are complimented by Jo Kilgour’s gorgeous lighting, which make all elements pop in stage-technicolour.

Watching Nell Gwynn and its depiction of the ripples when women are introduced to the stage, I couldn’t help but reflect on my experience earlier in the year when I found myself as an ally on a panel held at the Pop-up Globe, arguing why their all-male Shakespeare was such a retrograde – and boring – move. (I canvassed some of these issues in this piece). Shortly to debut in Melbourne, their shows this year featured an all-male Henry V and As You Like It (though they did have a female actor playing Desdemona in Othello…)

That’s a third take away from Gwynn’s historical mirror – for all that we are doing right in our entertainment in terms of casting and storytelling, there’s still a lot more that we could be doing better, in gender and intersectional issues.

The historical Gwynn performed on the stage for seven years, before ‘retiring’ to court life. Swale’s Gwynn returns to the stage for one more revolutionary act –not only to perform again, but to become a playwright (or at least, to write the epilogue of the play). It’s a decision that acknowledges that while visible representation and opportunities are crucial, the people who are writing and controlling the narratives are crucial too. Swale, with Briar Grace-Smith, number two female playwrights programmed in Auckland Theatre Company’s first Waterfront mainbill season, compared with four male (the writing and creative teams for ATC’s all too short Youth Festival Here & Now, were all female led). It’s a step in the right direction compared with previous all-male playwright seasons, but even theatre in Aotearoa is still waiting for a giant leap forward.

This production of Nell Gwyn is ATC at their best; a frothy and thoughtful act of period drama revisionism.

Nell Gwynn plays at the ASB Waterfront Theatre until 30 August. Details see ATC.

SEE ALSO: Theatreview.org.nz review by Nik Smythe

Leave a Reply