[A Case for Removing Commercial Imperatives for Artists?]

Would you accept public money to make an arts project if you had to return any profit that you generated back to the government?

Would you want to live on 200-something dollars a week (plus accommodation supplement) if it meant you could make your art without being forced by Work and Income to pursue a job outside of your artistic discipline?

Would it be lawful for the government to pass laws that set up such a system?

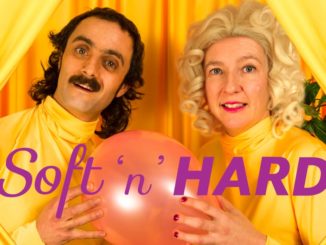

These were the issues presented last Thursday 22nd February in Binge Culture and Barbarian Productions’ It’s a Trial! for the Auckland Fringe Festival (a new version of a format that the team had premiered in Wellington in 2016). Justice Jody Ranzerson (Jo Randerson) proceeded over a case taken against the Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage questioning the legality of Government arts policies.

The Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage, of course, also happens to be our current Prime Minister.

At the Auckland Theatre Awards in December 2017 Jacinda Ardern stood in front of a room of theatremakers and declared “I see you”. She said:

“When we mention the word wellbeing and we think about the arts; when we mention the word community and we think about the arts. When we mention togetherness, identity, culture, our heritage, and we think about the arts. And I crave the day when we stop explaining ourselves and people just know it.” Ardern’s decision to take the arts portfolio (as Helen Clark had done in her time), offers hope for a renewed emphasis on the importance of the arts.”

But in interview “offcuts” published on The Spinoff, Ardern also warned the arts community:

“the budget is going to be pretty constrained, because we basically poured a huge amount into education and into families and incomes. I can be really honest that there’s no way to tighten their belts in the arts community. There’s just not. They run on the smell of an oil rag. Having said that of course, I support the finance minister in what he’s undertaking.”

The arts community are waiting to see whether Ardern’s support will go beyond the symbolic, and lead to meaningful resourcing of arts industries (Creative New Zealand, the Government’s arts funding agency, has in recent years have had their budgets be at the mercy of lotto ticket sales). Ardern’s comments signal we shouldn’t hold our breath in at least the first term.

But if the Labour led Government did decide to increase investment in the arts, or even restructure how this is delivered, what would they do? It’s a Trial! seized on comments made by Ardern elsewhere that “as long as we [are] constrained by the boundaries of a platform driven by commercial imperatives, we are personally not being as courageous as storytellers as we could be.” The value system implied here is that commerce blunts art, makes makers risk averse, maybe even prevents great art from being made.

Thus, in It’s a Trial!, applicant Ranya Tan-Manning (Anya Tate-Manning) seeks a judicial review questioning the lawfulness of the Government’s new policy to separate the creation of art from commercial imperatives.

Before you go wondering whether you missed this announcement in Labour’s first 100 days, or that the former president of the International Union of Socialist Youth is enacting their secret agenda of a radical Sovietisation of Aotearoa, let’s state this outright: this is a fiction.

Never mind that Ardern made these comments at a Screen Production and Development Association conference, Binge Culture and Barbarian Productions have extrapolated Ardern’s vision statement into a policy which goes ahead and removes the profit motive from government funded art.

In the show this leads to such delights as having the real Creative NZ CEO, Stephen Wainwright (called as a trial witness), disagreeing with fake New Zealand Government policies.

On the other hand, the obfuscation and confusion on the night was to such an extent that that one prominent industry person came up to the CNZ team to ask, “this isn’t really what’s happening, is it guys?”

What is happening (though details are scarce) is the reestablishment of the Pathways to Arts and Cultural Employment (PACE) scheme, which Labour committed to in their election manifesto, and was also up for challenge in the Trial conceit. Introduced in 2001 under PM Helen Clark, the scheme ran until 2011. Also known as the “artist’s benefit”, artists could be accepted to go on PACE instead of the then unemployment benefit. The payment was the same, but you were enabled to list the arts as your preferred industry, and in theory, not be pressured into taking that dishwashing job.

By 2011, access to the scheme was not universal, and the number of people on the programme was on the decline. It was put under review and discontinued. Then Social Development Minister Paula Bennett said, “as valuable as the arts are to our society… now is not the time to be turning down available work to follow an artistic dream.”

(By the way Paula, Taika Waititi used PACE while he was developing his film career.)

So both the fake policy, and the real yet-to-see-what-shape-it-will-take policy, were up for debate in a fake courtroom, with a fake judge, fake lawyers, but real witnesses (thus the CNZ CEO’s appearance in an Auckland Fringe show). The result was a sometimes jarring mix of legal spoofing and very insightful commentary. Court taker Courtney T. Aker’s (Maria Williams) many interruptions provided a delightful subversion of the stuffy legalistic rituals and point scoring lawyers.

Justice Ranzerson made the legally unorthodox (but theatrically rewarding) decision to have the judicial review tried by jury.

The selection of the jury was a less than vigorous process, with the cast pleading for audience members to volunteer themselves for this solemn duty with bribes of better sight lines. Unsurprisingly, the jury was almost equally stacked with lawyers and artists, although there was also an engineer and a beer brewer for good measure (interesting that they did not self-identify as artists). The jury’s task was to determine whether the Government policies met the “threshold of unlawfulness”.

Ms Rizmacken (Karin McCracken) had the floor first to make the case for the applicant. Humour was generated by the Justice’s constant undermining of Rizmacken’s competence and track record. Rizmacken’s contention was that it is wrong to divorce profit from the arts and rejects the “devil’s bargain” under which the artist is the only group in society asked to forgo profit. We wouldn’t prevent a furniture maker, who has received capital to buy timber, from selling the finished chair (although this analogy falls apart somewhat when you consider what happened to the chair makers after mass industrialisation).

The first witness was James Tito of the Modern Māori Quartet fame. The Quartet is recognised as a commercial success, but artistically Tito is proud of the sense of whanau that is created in each performance, and their promotion of Te Reo. Tito had gone to Toi Whakaari New Zealand Drama School, and there was a sense of pragmatism in forming the Quartet as singers are paid more than actors (dancers fall at the bottom of the fee scale in Tito’s hierarchy). That Tito had to state that it “should be normal to be able to pay rent as an artist” spoke volumes as to how often this was not the case.

In cross examination, Mr Bakensdale (Joel Baxendale) questioned Tito on whether the agencies and individuals with purchasing power and funding affected what gets made. Since Pakeha represent the majority audience, are there needs privileged, and work framed for them?

The second witness was Stephen Wainwright. Well versed in corporate-speak, he said the role of CNZ was to equip artists with the “tools to survive and even thrive”. He emphasized that both entrepreneurship and artistic skills are needed to survive in the industry. The commercial can be a powerful catalyst for artists to do something. He wants to grow the NZ industry and the market. He spoke of Edinburgh (home of the Fringe) as the doorway to the world, allowing artists to move beyond the domestic market to international success. He also seemed to think that the Cathedrals of Europe were relevant to the case, speaking reverently of their commission by the church as a commercial case study (I suppose we should look out for a press release announcing a forthcoming partnership between CNZ and the Catholic Church?). He talked of the benefits of venture capital in science funding, and called for a level playing field between science and the arts. His sensible conclusion (displaying leadership in pleasing everyone) was that there are “different good things” and the arts should pursue a range of models.

Bakensdale’s cross-examination led to this brilliant exchange:

Bakensdale: “Hard to have a creative vision if you don’t have anywhere to live.”

Rizmacken: “That’s not a question your honour.”

Ranzerson: “Can you put an upward inflection on it?”

The applicant Ranya was next to take the stand, and was quickly deemed a hostile witness after she changed her evidence (her actual reason for taking the case against the Minister was that she hoped it would create some publicity for her latest Fringe show, which, inconveniently, was actually playing in the Wellington Fringe and not Auckland). The hostile designation meant that Bakensdale was unable to question her, which he intimated was a potentially brilliant rouse. Ranya’s was a star performance in the witness box, all hankies and Puss-in-Boots eyes. She wanted the right to sell the IP to the show My Dead Best Friend, which had a season at Q Theatre last year. That show, she said, had “covered costs at a stretch, in that no one got paid.”

After a short break, it was over to Bakensdale to lay out his case. Massey University’s Dr Emily Beausoleil (who studies the democratic potential of art and uses words like “multivalent”) exploded out the binaries that had congealed around the case thus far. The social values that we use to assess the worth of an artistic work are contextually loaded and historically fluid (in other words, tastes change and likeability does not = value). We need to be aware of political and commercial agendas. She also spoke eloquently and compellingly of how art can let us see more than what we usually see. She also worried about the impulse for the artist to martyr themselves to their vocation. For Emily, the proposed PACE funding (which would presumably be equivalent to the Job Seekers rate) was not enough for artists to live on.

When Alice Canton, the final witness, was asked what the hurdles were for making art, she had a ready list at her disposal: “patriarchy, colonial structures, financial and emotional barriers.” She works a 9 to 5 job so she can be an artist outside of those hours. Canton was questioned about making her show OTHER [chinese] within capitalist structures. She had made a profit on the show, which she reinvested for costs in promoting the work at a New Zealand Performing Arts market. Canton conceded that she would consider selling the IP to the show, with certain limitations. The profit gained did not account for the hours of unpaid work in making that show, or all the shows she had made before that.

Bakensdale closed by stating that it was absurd to force anti-commercial art into a commercial world. His analogy was that it was like a Doctor making money through cosmetic surgery so that they could donate their time to do heart surgery on the side.

Karin McCracken (who has a Law and Arts degree) played the consummate lawyer, building the case, chipping away at her adversary. By the end the Justice could not stop singing her praises. Baxendale played the slippery one, getting pinged for leading questions, and occasionally losing his train of thought (Maria Williams went to the rescue, located his choo-choo train, and delivered it back to him, in one of the many surreal moments during the trial).

The Justice summarised Bakensdale’s case as funding being “better than nothing”. However, once you get past the default capitalist response that of course people should be able to make money from their labour, there is arguably more merit to the model than what Baxendale/ Bakensdale managed to make of it.

Both Tito, called for the prosecution, and Canton, for the defence, said that they would be okay with their profits being returned to the funding pool (if they had received government funding). Canton liked the idea of other artists being able to benefit.

Because what seemed to get lost in the trial is how little profit artists actually see. The headline figures might be that New Zealand’s creative industries are the fourth biggest contributor to this country’s GDP, but for many, the arts is something they have little choice but to do on the side, funded by their ‘sensible’ job.

Theatre, for example, often involves a false economy anyway. Box office income rarely begins to cover costs, the industry is highly subsidised, and independents often work far below fair wage (if they pay themselves at all).

You begin to wonder what would happen if we did have a complete rethink of our approach. If everyone had a Universal Basic Income, would we have more artists?

This isn’t a place It’s a Trial! got to. The murkiness of the actual proposals on trial, and the lack of a clear-eyed explanation at the beginning of the trial of our current arts infrastructure, limited the potential of the debate. It was only late in the trial that it was clarified that not-for-profit organisations would be able to reinvest any earnings (which is how much of the theatre industry works anyway), and only independents would have to return profits. There was also little distinction between artistic genres (film, music, theatre, visual arts etc.), and the ways these operate differently. The potentials and drawbacks of the PACE scheme were given short shrift.

While the specificities and complexities of the case were a blur, we did get to engage with the broad philosophical questions. Who decides what great art is? Who decides which artists should be funded? What is fair compensation?

There is some (intentional) tension in this work sitting within a Fringe Festival, in which the majority of artists are making work with next-to-nothing, for next-to-nothing (did you see that article that went round about Fringes being like Uber, dependent on the exploitation of artists?). Tickets to The Trial were sold at $18-30 (the pricier end of Fringe), though playing for just one night with the limited occupancy of Samoa House would have rather curtailed any profits. Binge Culture and Barbarian Productions have also just run a successful crowdfunding campaign on Boosted to support the work. With many artists donating to this cause, it appears to be another example of industry-subsidisation, given by those with the least money.

The Boosted page states:

“Ultimately we would like to get the show to a place where we could respond to issues as they arise, help communities facilitate debates they need to have, and source all the expert witnesses that form such a large part of the show from within the audience.”

This is (if I may venture such a judgement) a valuable mission, and I’m excited about the idea of the show continuing to be adapted for different topics and conversations. There is a lot of appeal in the theatrical play of the format, although the most compelling moments are when the lawyers ask the right question to provoke insights from the experts. The focus now needs to be on getting to the heart of the issues.

And the verdict? We had split jury. Appropriately, they determined it wasn’t either lawful or unlawful.

But was It’s a Trial! great art? The jury’s still out on that one.

Leave a Reply