[What would Bruce do?]

It was a highly symbolic gesture to begin New Zealand Theatre Month in Auckland with a tribute to Bruce Mason, held at Takapuna’s Bruce Mason Centre.

In the words of Roger Hall (the MC for the tribute and founder of the month), Bruce Mason was the “Father of New Zealand theatre and plays.” Historian Peter Harcourt said that if the change in New Zealand theatre from being a “Britain of the South Seas” to having a “more representative style of ‘Ao-tea-roa’” could be “credited to one person, the man who deserves it is Bruce Mason. (1) Mason’s early plays, produced by Wellington’s Unity Theatre, dealt with confronting New Zealand issues: The Bonds of Love (1953) sexually interprets the bondage theme of the (not then official) national anthem and The Verdict (1955) was based on the topical Parker-Hulme murder trial. Mason turned his attention to the status of Māori in New Zealand society in The Pohutakawa Tree (1955) and while a television version was broadcast by the BBC in the UK, professional productions within New Zealand were not forthcoming. At the end of the 1950s Mason was disillusioned, writing that he was at the “end of my tether attempting to earn my living entirely by writing and acting. How was one to make one’s living doing the thing one wanted to do and one felt one was for…?” (2)

Mason’s breakthrough was The End of the Golden Weather (1959), his solo show which equated the burgeoning maturity of its 12-year-old protagonist with New Zealand’s emerging (Pākehā dominated) national identity. Golden Weather made a big impact on playwright-to-be Roger Hall, who had emigrated from England in 1958 aged 19. In his autobiography Bums on Seats, Hall wrote that the play “described a childhood unfamiliar to me, but one that was bought vividly alive… It was not only the best night I’d had in a theatre in New Zealand, it was one of the best nights I’d had in a theatre anywhere.” (3) Mason would go on to perform Golden Weather over 850 times through his career, right up until the end. My seat partner at the tribute, who had seen many of Mason’s works, told me how Mason kept performing despite having jaw cancer, and how we would sit there holding one side of his face up, which she remembered as being very brave. Te Parenga was the setting of Golden Weather (and The Pohutakawa Tree), Mason’s fictional placeholder for Takapuna beach. Thus, Takapuna’s performance venue, which opened in 1996 was named the Bruce Mason Centre. Over the last decade, Stephen Lovatt has made a Christmas day tradition of performing a seasonal extract from Golden Weather at the beach.

(If Mason is the father of NZ theatre, the mothers of New Zealand theatre would be the crime-writer Dame Ngaio Marsh, who was a mainstay of Christchurch theatre through the 1940s to 60s and toured productions to Australia, and Nola Millar, who was the president of Unity Theatre, helped form the New Zealand Players company, was a director over four decades, and originated the New Zealand Drama school.)

Roger Hall gave his own performance as part of the tribute, dramatically reading a war of words between Bruce Mason and visiting UK actor Donald Wolfit that played out in the pages of the Dominion newspaper. Mason was the resident theatre critic; while he had plenty of praise for Wolfit’s programme of Shakespeare scenes, Mason had some pointed criticism on the performative choices. Wolfit was furious. What followed was a series of Shakespearean shade, spat, and counter-attacks through letters to the editor – the newspaper coverage a stark contrast to the level of media visibility theatre receives today (although the tone of the debate not unlike something we might see in Theatreview’s comments section today). Wolfit taunted that perhaps New Zealand didn’t want any professional theatre at all (Hall taking pleasure in his performance in reproducing the RP opprobrium) and that New Zealand theatre critics were becoming world famous for their rudeness. This fame was news to Mason, who insisted that New Zealand audiences were not “ignorant peasants.” The correspondence is a fascinating window into the late 50s period – this public spat was an insistence for quality with colonial implications. Mason had dared to criticise the touring British star – and the status quo that privileged overseas work as far superior to anything that could be produced locally.

As a playwright, Mason had a firm nationalistic agenda. This was showcased at the tribute through short performances from two of his plays, with direction by Theatreview editor and The Plays of Bruce Mason author John Smythe. The first, Hongi, was written for Māori Opera star Inia Te Wiata and was recorded as a radio play in 1968 (it has still never been produced for the stage). Smythe chose for performance the key scene where in 1820 missionary Thomas Kendall (Roy Ward) introduces Rangatira Hongi Hika (Haami Piripi, a direct descendant) to King George IV (Andrew Grainger). Hongi undercuts the royal etiquette (introducing himself with a “How do you do Mr King George?”) and George finds himself taken with the chief with 9 wives. The scene exemplifies Mason’s wit and skill, both investing in the historical weight of this meeting of civilizations and undercutting it with delightful bathos.

This scene was followed by a monologue from Mason’s last play, Blood of the Lamb (1980), performed by Inia’s daughter, the incomparable Rima Te Wiata. Written in 25 days as a vehicle for three female Court Theatre company actors who were not cast in the company’s other productions, the play worked through national and gender issues in focusing on the relationship of two lesbians, one of whom lives as a man, and their daughter. Smythe’s selection was one of the most disturbing speeches in the NZ canon – with mounting dread Wiata describes a sexual assault which comingles with the culling of a lamb. Wiata builds towards the final devastating line – the realisation of “what men are and what my country is… a bloody carnal house.”

In the 2000s Auckland Theatre Company produced some fine revivals of The Pohutakawa Tree, The End of the Golden Weather and Awatea. Mason has cast a long shadow of our national theatre, although in my article for The Pantograph Punch about Carl Bland’s Te Po (which sampled Mason’s life and characters), I wrote that “Bruce Mason has been missing from our stages for quite some time. If Mason was to make his second coming now, he might indignantly cry, in clipped tones: why are you still not putting on my plays?” New Zealand Theatre Month, with events like the tribute to Bruce Mason, presents an opportunity to guard against our historical amnesia, to return to Mason, to return to our canon, to better understand where we have come from, and where we are going.

Red Leaping through History

One of Mason’s greatest contributions, despite its imperfections, is his engagement with New Zealand’s biculturalism. Mason’s nationalism understood the necessity of telling Māori stories on the stage, for his society to grapple with the relationship between tangata whenua and Pākehā, and he anticipated the time when Māori writers would be able to tell their own stories through the theatre. This was answered in part by the Māori protest movement from the 1970s, which saw work from a number of Māori theatre makers, including Rore Hapipi and Jim Moriarty, who created the Te Ika a Maui company (which staged Hapipi’s landmark Death of the Land in 1976, subsequently adapted for television), as well as Harry Dansey, the Maranga Mai collective, and Don Selwyn.

Mason’s bicultural concerns – and the responsibilities of representation – have re-emerged in Red Leap Theatre’s latest production. Kororāreka: The Ballad of Maggie Flynn recasts our national history, putting Maggie Flynn at the centre. An escaped convict criminalised for prostitution, she captains a whaling vessel, integrates with local iwi, and ends up running a brothel in Kororāreka, which, if anyone has ever taken NZ history at school (sadly not enough of us it seems!) will know, was known as the “hell hole of the Pacific.”

Red Leap Theatre’s prestige was built off the success of their debut production The Arrival (2009), a visual theatre adaptation by the founding Artistic Directors Julie Nolan and Kate Parker of Shaun Tan’s graphic novel which wordlessly presented a migrant experience in a fantastical land. The production is still in Red Leap’s repertoire, having recently played in Brisbane. Subsequent productions Paper Sky, Sea and Dust Pilgrim continued to develop Red Leap’s physical, playful and profound image-based theatre style, though never matched the narrative cohesiveness of their debut production. The company’s kaupapa has crystallised to become dedicated to “telling women’s stories and celebrating women’s talents.” Reacting to a script by Paola Rotondo (a new development for the company), Kororāreka sees Red Leap on the top of its form and, in its negotiation of the Pākehā and Māori relationship, is its most locally resonant work.

Rotondo (an Italian born Kiwi who previously co-wrote and toured Strange Resting Places with Rob Mokoraka about the Māori battalion) alludes in the programme to the difficult creative journey of the project. Rotondo had been inspired by the Irish Catholic lineage of women on his mother’s side, and researching and writing this story was motivated by a “personal desire to ‘belong more’ to Aotearoa” and link his tangata whenua children’s whakapapa to his mother’s. Rotondo writes that, “as a male, European writer, writing both female and tangata whenua characters it was only natural it would give birth to discourse. The robust debate has been deeply challenging and very painful at times for both women and Māori. I was challenged and asked to acknowledge different perspectives, history, my privilege, and inherent bias.” Kororāreka has had a number of eyes on the script, from director Julia Nolan, dramaturg Gary Henderson, Pou Awhina Amber Curreen, Māori advisor Waihori Shortland and the cast and creative teams. Development casts included male actors, before the creative team settled on five wahine performers. The debut Q production last year featured a sculptural scaffold centrepiece that the cast pushed around the stage and climbed like a jungle gym. This year, the staging aesthetic has been entirely rethought and simplified; what they’ve lost in majesty is made up for functionality with a series of black boxes of different shapes that create their desired spaces and levels.

The 2018 tour has been to Napier and Wellington, and after Auckland (I saw it at the Māngere Arts Centre and its playing Albany on 7th September) the production continues to Tauranga, Hamilton and Whangarei.

The cast begin unified in a wero to the audience, light enveloping them. Maggie (a role fiercely shared by Victoria Abbott and Alison Bruce) makes an immediate claim of belonging – the “land is my body” – and a statement of intent – “My name is Maggie Flynn, and this is my story.” As characters, the cast fracture – a sea shanty and a karanga are performed over the top of one another, both sides straining to be heard.

This play is a fiction, but borrows from historical fact (in Maggie there are echoes of Charlotte Badger, one of the first Pākehā women to have lived in New Zealand). Maggie’s story is one of reversals, upending the status quo. She arrives in Aotearoa in 1820 the captain of a whaling ship after her husband died during the journey (exposition is deftly handled through interactions with the spirit of Captain Riley, whose body has been pickled in a barrel of whale blubber). Lawless New Zealand appealed to the escaped convict, but before even making landfall she encounters the existing rangatiratanga. There is cultural tension over tapu and Riley’s body – the local iwi want a tangi, while Flynn retorts that “this is a fucking wake.” The ownership of the ship is claimed by the rangatira (Hinerongonui Kingi), and after disrespecting his mana, Flynn is taken to their village to teach the tamariki English.

Maggie gains the ear and trust of the rangatira, insisting to the chief’s sister (Amber Curreen) that “he’s just a man like any other” and therefore she knows how to deal with him. While there’s an element of pragmatic survival to Maggie’s strategy, we also glimpse the possibility of meaningful integration in her adoption into the tribe, and she is given her own moko. Meanwhile, she is conferred residential status as a “white New Zealander” by a European mob who decide she needs to be saved from the savages.

History marches on, foreclosing possibilities of what might have been. The play’s final section takes places in 1845, post-Treaty (Rotondo places Maggie in the middle of this – she reports that she instructed Governor Hobson, “don’t fuck it up”). Now Maggie runs a brothel in the Kororāreka settlement, her survival instinct quashing the dissonance of now trading in flesh and placing others in the position where she once was. As compelling as Maggie’s narrative is, and despite the company’s engagement with cultural and feminist discourses, by placing Maggie at the centre, the production still side lines the tangata whenua characters. The position of the chief’s sister, who works with Maggie in the brothel, is one of the play’s most interesting threads, but the rollicking narrative provides little space to hear more of her story. The production raises ongoing questions for its audience of what stories are told about our past, and whose perspectives are privileged.

Red Leap’s approach is sly and inventive, using anachronistic props (microphones, Pump water bottles, ping pong balls) in surprising ways. Kororāreka takes a new look at the myths of the contact period, positing that something of the spirit of Maggie Flynn, who stood her ground to the very last breath, lives on as a vital part of the New Zealand psyche.

The Feeling of an Audience

Mrs Krishnan’s Party is a rarity in New Zealand theatre: a sequel. Roger Hall wrote Spreading Out (2004) as a sequel to Middle Age Spread (1977), Stephen Sinclair and Anthony McCarten followed their hit Ladies Night (1987) with Ladies Night 2: Raging On (1993), and Renée wrote a Wednesday to Come trilogy (from 1984). But mostly, individual plays to do not stick around long enough in the theatre going consciousness to warrant a sequel.

Mrs Krishnan’s predecessor, however, has never really left our consciousness. Since its debut over twenty years ago, Indian Ink Theatre Company’s Krishnan’s Dairy (1997) has been a prominent fixture in the company’s repertoire: it’s toured nationally (most recently in 2015) and globally (from Edinburgh Fringe in 1999, where it won a Fringe First award, to India in 2016).

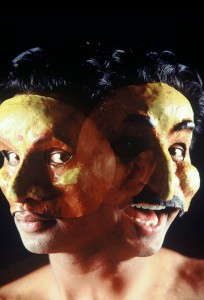

You don’t need to have seen Krishnan’s Dairy to enjoy Mrs Krishnan’s Party, but for audiences who do bring an awareness of the first play into the second, there are further depths of poignancy and connection that become available. Where the first play was set in the Diary front shop, Party takes us behind-the-scenes into the store room. Dairy asked us how we quantify love, contrasting the arranged marriage of Gobi and Zina with the epic obsessive love story of Shah Jahan, who constructed the Taj Mahal as a monument to his deceased wife, Mumtaz Mahal – a tale narrated by Zina to baby Apu. Gobi is shot and dies at the end of Dairy, connecting with New Zealand’s shocking history of violent crime against dairy operators. Zina, who had bickered throughout the play about wanting to return to India, resolves to stay and dedicate the diary as a living monument to her husband’s memory. Bear in mind that all of this had been performed by Jacob Rajan, skilfully switching masks and voices with such ease and speed your mind would trick you into seeing Gobi and Zina interacting with each other on stage. In the final scene of the play, Rajan appears without a mask as an eighteen-year-old Apu.

Mrs Krishnan’s Party takes place a few years after this scene. Apu has moved out, but Zina is anticipating his return for Onam. She – and we – still feel the absence of Gobi. She turns on the radio and ‘I Say a Little Prayer’ plays (audiences might remember as the song Gobi sung throughout Dairy). Mrs Krishnan is overcome, grief reaching out to her through the years. Mrs Krishnan’s Party asks us about change and rebirth, if it is possible to love again. Mrs Krishnan’s boy is grown, she is considering selling up, and there appears to be a suitor on the scene – not that she’s willing to entertain that. This time the domestic story is complimented by the tale of King Māveli – the harvest festival Onam celebrates his return from the underworld once a year.

Mrs Krishnan’s Party represents a return to Indian Ink’s past (and a local story, after taking a global outlook in recent plays Kiss the Fish and The Elephant Thief) and an investment in Indian Ink’s future – the play was created for the incredibly talented Kalyani Nagarajan, who takes the title role.

Indian Ink also explore a participatory/immersive form. We are welcomed by James (Justin Rogers), Mrs Krishnan’s boarder, and we find ourselves cast as guests at Mrs Krishnan’s Onam celebrations (which turns out is news to Mrs Krishnan). The whole show takes place in real time. Dhal is cooked for us (and by some of us!), the dramaturgy of the play needing to incorporate preparation and cooking times. Like Red Leap’s Kororāreka, this tour of Mrs Krishnan’s Party is a return season, its recipe having been further honed since its debut season last year.

The result is one of my favourite New Zealand productions of all time. Krishnan’s Dairy holds that distinction too, but Party makes it way there on its own merits. Theatre relies on the active imaginative collaboration between the performers and the audience – both need to be invested in the world of the play in order for it to come to vivid life. Writers Jacob Rajan and Justin Lewis take that principle and thicken it. By fully engaging us as participants in the backroom of Mrs Krishnan’s Dairy, a wonderful sense of community is created – one that is unique to each performance. Mrs Krishnan’s Party is a beautiful communal experience that gently warms the heart and restores your belief in the unique magic of live theatre.

10 Minute Experiments

Short + Sweet Theatre’s tagline is “taking over Auckland ten minutes at a time” – its programme features a selection of 10 short plays, kept to a strict time limit of ten minutes each. Ten is an especially significant number this year as this is the tenth edition of Short + Sweet in Auckland [Short + Sweet will be celebrating their 10th anniversary in 2019 as their first season was considered a pilot]. An International Festival originating in Australia, Short + Sweet Theatre arrived in Auckland in 2009 where it played at the Herald Theatre, but it has since found a firm home at TAPAC across from Auckland Zoo. This year there are two lots of 10 plays playing for three nights each (the first programme contained eight plays by local writers, with two from the international Festivals). There are other Short + Sweet offshoots too – this year Auckland is also hosting Short + Sweet Dance and Film.

In Theatre line up the genres are varied and quality of the work is often uneven; more than once I find myself sinking down into my seat in cringe extremis, but others have me sitting up in delight. Marvellous Theatre Group, a troupe of senior citizens, have been regulars at Short + Sweet and their entries are always anticipated. This time they are parodying Milton, following the story of the flora that have been banished from the Garden of Eden. Meanwhile, cultural identity and the migrant experience was a prominent thread in a number of plays in the first programme, which also featured time travel and humans playing cats (although no singing, fortunately?). The next ten plays open on Thursday, with a gala featuring the best of both programmes running on Sunday.

Short + Sweet Theatre’s decade in Auckland has offered a vital opportunity for practitioners to experiment in a low risk environment, to try their hand at writing, directing and acting. As such, it connects back to the British Drama League competitions that ran in New Zealand from 1933, in which local writers across the country submitted One Act plays for judging and performance by Amateur societies – another reminder of the long history of theatrical expression in New Zealand.

Theatre Scenes Picks for Week One of New Zealand Theatre Month (Auckland)

- Bright Star by Stuart Hoar, presented by Plumb Productions @ Herald Theatre (4 – 16th September)

- Orientation by Chye-Ling Huang, presented by Proudly Asian Theatre @ Q Theatre (5 – 15th September)

- Cradle Song by Albert Belz, presented by Te Rehia Theatre @ Corban Estate Arts Centre (5 – 8th September)

- Kororāreka: The Ballad of Maggie Flynn by Paolo Rotondo, presented by Red Leap Theatre @ Massey University, Albany 7th September)

- Short + Sweet Theatre @ TAPAC (Theatre Programme 2 6 – 8th Septmember, Gala Final 9th September)

Discover what else is on around the country at the New Zealand Theatre Month website.

Previous New Zealand Theatre Month Coverage:

Leave a Reply