The good news: For the first time in four years, 2023 was marked by the absence of widespread disruption and cancellations of performing arts events caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Buoyed by Government investment, festivals were back in force up and down the country. There were plenty of sold out shows. Theatre is back, baby!

The not-so-good news: Extreme weather events replaced Covid as a major disruptor. Short-term funding injections have failed (surprise, surprise) to lead to long-term sustainability, and public investment is contracting. Some treasured institutions closed this year, while others are hanging on by the skin of their teeth. There’s been a change of Government, led by a major party lacking an arts and culture policy. Everything costs more, and many shows struggled to find their audience. Theatre is in a holding pattern.

Yes, 2023 was a glass half-empty/half-full kind of year for Aotearoa’s theatre and performing arts. While we can be grateful that Covid-19 didn’t take out shows in the way that it did between 2020-2023 (notwithstanding some cancellations and delays due to illness, including the first week of Basement’s Christmas Show), the many challenges exacerbated by the pandemic still loom over the sector.

Aotearoa’s theatre sector has its own kind of Long Covid: general exhaustion, a sluggish recovery, ongoing issues without an immediate fix or support plan. And a worry that we might not ever properly recover. (And let’s also recognise those in the arts community who’ve been mostly invisibly negotiating their own Long Covid, and its impact on their lives and creative practice – I’m one of them).

There’s much angst in the US and UK about the health of the performing arts industry. In an article headlined, ‘A Crisis in America’s Theatres Leaves Prestigious Stages Dark’, The NY Times reported that “there is less theatre in America these days.” Regional theatres are “staging fewer shows, giving fewer performances, laying off staff and, in some cases, closing”. The LA Times baldly stated “the theatregoing habit is broken”. In the UK, The Guardian reported that “theatres face closures and staff shortages” and “bosses of smaller UK theatres quit in droves”. A former CEO of Arts Council England warned “we are approaching a doom loop where less money, less certainty in future funding and a hostile environment to inquiring ideas leads to less risk-taking and new work. That in turn leads to declining new audiences, smaller box-office receipts and a less compelling cultural economy.” Lyn Gardner wrote for The Stage that ‘Theatre needs a long-term strategy if it is to survive these crisis years’. Reporting from Scotland, the Financial Times asked ‘Fringe theatre is in crisis. Can anything be done?’. New Zealand’s headlines aren’t as bad as all that – yet. We can’t be complacent.

Let’s do another one.

The good news: In November, Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage highlighted that Aotearoa’s arts and creative sector contributes $14.9 billion to the country’s GDP, making up 4.2% of the total economy. Despite pandemic challenges, the creative sector grew by double the rate of the economy as a whole (10% to March 2022 compared with the total economy’s 5.3%).

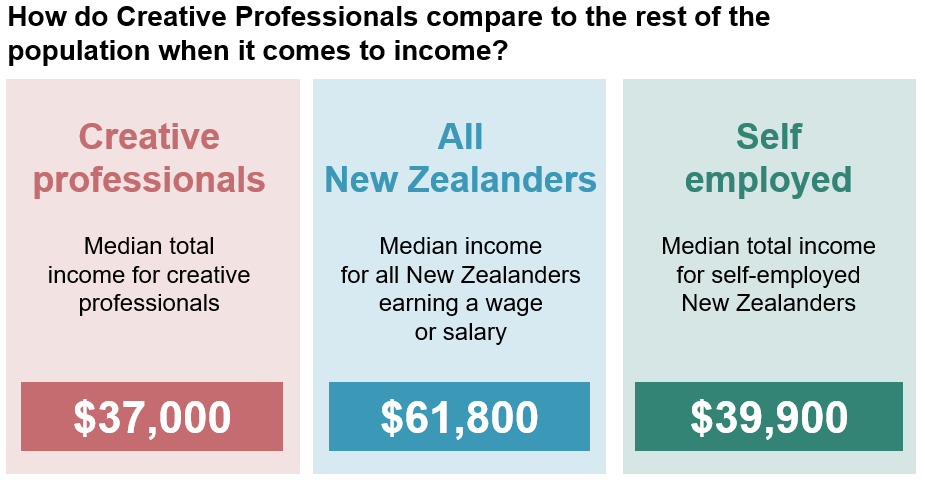

The not-so-good news: In May, Creative New Zealand and NZ on Air released a report confirming that incomes for creative professionals have barely moved over the past four years. The median income for salaried/waged NZers increased by $10,000 from $51,800 to $61,800 between 2019-2024. Meanwhile the TOTAL median income (including income from other jobs) for creative professionals went from $35,800 to $37,000. The median income for creative work alone is just $19,500. In the performing arts, median income per hour was $21.40 (compared with $29.67 for working New Zealanders), with a total median income of $36,500.

Dig further, and we find that there’s a 32% gender pay gap, with female creative professionals earning “significantly less than their male peers – $16,500 a year from creative income alone”, while “Deaf or disabled artists earn on average $15,000 a year from creative income alone.”

Also troubling: 1 in 2 creative professionals reported experiencing burnout over the past year (whilst 79% reported either experiencing burnout or coming close to burnout).

There is a stark disconnect between the value created by arts and culture, and how the people that create arts and culture are valued.

Why? After all, there’s a clear economic return for supporting performing arts, which in turn stimulates the hospitality sector and other businesses. This year’s pro-amateur production of Wicked in Pōneke was credited for driving business in the city. The Post reported (9th Sept, print) “After FIFA’s women’s world cup failed to score with some of Wellington’s hospitality outlets, the witches of Oz have brought in the crowds,” boosting “Wellington tourism, with people coming into his bars before and after the show, ordering cocktails and sharing plates.” One hotel owner said, “It was better than that soccer thing.” (A shame then that pro-amateur productions like Wicked don’t adequately compensate most of their company.)

Even more important than the economic is the social return, with performing arts boosting wellbeing and connecting community.

We’ve got the data – the good and not-so-good. We need to keep acting on it.

Now, let’s take a look at some of the major moments in Aotearoa’s theatre and performing arts over 2023:

THE CURRENT CLIMATE

2023 began with extreme weather events including Cyclone Gabrielle and major flooding, causing fatalities and massive damage. The storms had big impacts on arts events, particularly in Te Tairāwhiti and Te Mātau-a-Māui (Napier’s Art Deco Festival was cancelled entirely).

In Tāmaki Makaurau, numerous events during Auckland Pride were disrupted, including Festival of Live Art (F.O.L.A), following a power outage at Basement Theatre caused by the cyclone. As Erin O’Flaherty noted:

this was the third time F.O.L.A suffered from disruptions, with the previous two times seeing the festival cancelled all together due to Covid. The forces of nature continue to be relentless, an ever-evolving wave of small apocalypses, and the arts are not the only industry to suffer as a result. We have seen countless postponements and cancellations, and it’s surely been a disheartening time for many – not to mention, a surreal and scary time for some.

Erin was happy to report the final and only night of F.O.L.A. which went ahead was “buzzing with bodies and music and visuals.”

CLOSING NIGHT

Wellington’s Summer Shakespeare production of The Tempest lived too much up to its title, with multiple weather cancellations over its season. Tragically, this eco-minded production would become the final ever Summer Shakespeare. “After four decades of enchanting audiences with captivating performances of Shakespearean plays, the Wellington Summer Shakespeare Trust has made the difficult decision to close its doors. This closure marks the end of an era for one of New Zealand’s most beloved theatrical traditions” came the announcement in June. Specific reasons weren’t forthcoming – “careful consideration of various factors… changing circumstances and shifting priorities have made it increasingly challenging to sustain the organisation” – although The Tempest’s experience certainly highlights the challenges of holding outdoor events in our climate change era. Miranda Harcourt told The Post that the closure of Wellington Summer Shakespeare was a “great tragedy” – “productions kick-started so many Kiwis’ careers in the arts – from actors to producers to directors to designers.”

It looked like a similar fate was to befall Manawatū’s Summer Shakespeare, after Massey University pulled support. But unlike Wellington’s Shakespeare, there was an opportunity to rally council and community support. RNZ reported, ‘Summer Shakespeare saved, for now, as Massey University stops funding’.

When even organisations that cater to one of Aotearoa’s most popular playwrights (sorry Roger Hall) find themselves in trouble, these are symptoms of a deeper malaise. University of Auckland’s Summer Shakespeare ended pre-Covid, superseded by the then Pop-up Globe juggernaut. Speaking of, like Sebastian in Twelfth Night, the Pop-up Globe appeared back from the dead this year. This was courtesy of receivers who ordered the resurrection of its trading name to pay back creditors, following Pop-up’s liquidation in 2021. While the scaffolded Globe venue didn’t return (for now), a successful extended season at Q Theatre reflected the company’s enduring appeal to the general public. Not everyone welcomed Pop-up Globe’s return, which had come as a surprise to some creditors, left out of pocket and still without any guarantee of being paid back. A creditor told The Spinoff, “many of us extended a huge amount of goodwill towards Pop Up Globe… It doesn’t feel that goodwill has been honoured in the way this has played out.” More seasons are coming in 2024 – let’s hope Pop-up Globe heeds Shakespeare’s advice: “Words pay no debts, give her deeds.” While a remarkable 90% of work on our professional stages is of New Zealand scripts, New Zealanders aren’t done yet with Shakespeare it seems, further proved by the nimble Barden Party, touring the country with garden performances of Shakespeare’s plays.

Theatre for young people also experienced significant blows. Following last year’s closure of Young & Hungry, 2023 saw the shocking closure of the National Theatre for Children after 25 years, “the latest gut punch for underserved children’s art in New Zealand.” The decision was notable for the lack of advance public notice or effort to try and save the organisation, with poor transparency around the reasons for its closure. City council controlled Experience Wellington, which will continue the Capital E brand and space without the National Theatre, told The Post that “it was stepping away from delivering the theatre’s programme to ‘better focus on delivering remarkable experiences for the people of Pōneke’.”

After 25 years, the arts community deserves a proper explanation and accountability. Whilst the organisation had an operating deficit, funding from Creative New Zealand was secure. As Performing Arts and Young People (PAYPA)’s Dr Kerryn Palmer told The Post, “to not have a national theatre for children puts us behind other countries a millionfold. … It’s really dire and disastrous.” Former Capital E director Stephen Blackburn shared with The Big Idea a concern that “the funding will not be ring-fenced for new work for young audiences, an audience already badly underserved in the arts ecosystem. I have always advocated for a sports-like approach to arts funding. Invest in the young teams that build the future elite athletes or passionate sports attendees. Same with the arts.” With the loss of the National Theatre for Children, a new national approach and commitment for supporting theatre for tamariki and rangatahi is critical: the future is at stake.

A long-brewing crisis at our country’s largest professional theatre, Court Theatre, exploded in 2023 with revelations of sustained workplace bullying by its Chief Executive Barbara George and a financial crisis. A remarkable 22 current and former staff talked to The Press, with 20 saying George “had to go.” More than 30 Court Staff quit during George’s five year tenure. “The Court Theatre is the most toxic environment that I’ve worked in, and it’s painful to see how many people are being damaged and hurt,” said one former employee. The Press also reported that Court was “running out of cash” and in deficit, with ticket sales down a third compared with the previous year. The last show to have made money for the theatre was the 2020/21 summer season of Jersey Boys.

Reviewing Dance Nation, Josiah Morgan took the opportunity to reflect on Court Theatre’s role in the wider arts ecology of Ōtautahi Christchurch:

I can’t help but note that there must have been less than a hundred people in my audience – and many of them left at half time. This indicates that the marketing for this show has been misdirected, and perhaps that the audience had no idea what they were getting into. The Court Theatre are continuing to take bold steps in their role as taste-makers with this year’s programme. They need to hold the line going forward: be brave, and the audience for this work will step up. At the same time, Court Theatre need to support the wider arts ecology in Ōtautahi – the arts ecology that primes audiences to expect, appreciate, and want to see work like this. I’ll say it again: it’s the strongest work staged at Court Theatre this season. It’s just a shame there were so few people there.

After a turbulent and traumatic year, healing is needed under a new Chief Executive as the Court continues to ready itself for a move into its new CBD theatre. Meanwhile Little Andromeda, a vital venue for Ōtautahi’s independent performing arts, secured a “last-minute reprieve” from closure after receiving Ministry funding – the last of the Covid recovery support. Whilst short-term Covid support ensured arts organisations were able to get through the first years of the pandemic, now this investment has ended, there is a real risk that we could see more organisations fold over the coming years.

Arts on Tour took a reduced performing arts programme to New Zealand’s rural areas, after loosing out last year on multi-year funding from Creative New Zealand. In the lead up to a crucial funding decision, TVNZ Sunday ran a story on Arts on Tour’s work, focussing on Jackie Clarke’s tour to Waikaia in Southland. “I couldn’t do this without this scheme. I couldn’t take this risk or come to these places” said Clarke. Sunday placed Arts on Tour in the context of wider cuts to rural services that glued communities together, like banks and shops, with cuts running “pretty deep in rural communities.” Southland sheep farmer Bevan Hopcroft spoke up for the importance of rural tours: “You take the wife along, and it’s date night. You have a glass of red, talk to the neighbours, you haven’t seen the neighbour for a couple of weeks.” Asked how important shows like Clarke’s were to binding the community together, Hopcroft replied, “I reckon that’s a real important one. To get a show like that turn up, absolutely brilliant”. Arts on Tour received the short-term funding, but a long-term plan for supporting rural arts is needed.

Arts were also on the line in our biggest city, with a coalition of arts and community organisations banding together to ‘Stop the Cuts’ and reverse Auckland Mayor Wayne Brown’s proposal for $20million+ cuts to the council’s arts, culture and community funding. Following an influx of public submissions, Brown conceded that “there is just about a consensus that Auckland Council should not proceed with all the cuts to social and cultural spending.” There were significant wins, with almost all of the Council’s arts and community services funding reinstated. However, Tataki Auckland Unlimited, which brings big events to the city and umbrellas Auckland Live (which runs the Council’s performing arts venue), has faced spending cuts and job losses, limiting its ability to support the wider Auckland’s arts ecology. Meanwhile, Rotorua City Council also proposed a “pull-back on arts and creative communities funding”. With local council costs continuing to rise across the country, local communities need to be ready to ensure elected councillors protect arts and culture investment.

I found myself campaigning to stop proposed cuts to my own workplace at Te Herenga Waka–Victoria University of Wellington, with theatre one of many programmes targeted for cuts. The proposals would have wound back 50+ years of growth for New Zealand’s oldest university theatre programme (you can read about the #SaveVUWTheatre campaign on The Big Idea). While we were successful in saving the programme, it illustrated the vulnerability of creative arts in our tertiary system. And there are urgent questions about safeguarding the role of arts in our education system, with the new Government’s emphasis on an hour of reading, writing and maths per day. The arts should be part of this equation – for example, children do better at maths when music is part of the lesson. Why not an hour each of reading, writing and maths, and arts every day?

So, plenty of not-so-goods here: threats to arts education, young and rural audiences underserved, financial challenges. We’ve made it through the pandemic, but with reduced funding and resources we’re at real risk of weakening or losing more of our key arts infrastructure. It’s almost as if we need a national arts and culture strategy, to help us prioritise resources and “boost access and participation in arts, culture and creativity for the benefit of all New Zealanders.”

THE ART OF POLITICS

Australia showed us how it can be done, releasing the Revive National Cultural policy. Budgeted for A$286 million (NZ$315 million) over four years, Prime Minister Albanese promised to “put the arts back […] at the heart of our national life.” This was a major national arts and culture policy with popular public support – a win for the Government, a win for the creative sector, and a win for the country. “Arts job are real jobs” said the PM; “You are essential workers” added the Arts Minister.

I argued on The Conversation that:

Revive’s five policy pillars provide a useful starting point for a conversation on what a national culture policy could look like in New Zealand: First Nations first; a place for every story; the centrality of the artist; strong institutions; reaching the audience.

A national strategy for Aotearoa could direct resources towards where they could have the most impact and harness the wellbeing benefits of ngā toi, or art and creative expression… Arts and culture are not a nice to have: they are essential to who we are as individuals and as a community. Government investment in arts and culture is also an investment in education, health and employment. We need to make breaking the cycle of crisis in Aotearoa’s arts and culture ecology an election issue.

But arts, culture and creativity barely featured in New Zealand’s election campaign. Labour released an arts policy at the tail end of the campaign, belatedly pledging to “explore an Aotearoa Arts Strategy.” The Greens wanted to unlink arts funding from gambling revenue. Act wanted to defund the Film Commission. National didn’t have an arts policy at all. It is shameful that a major political party could go to the election without one. As a sector, we cannot allow this to happen again.

Why did it happen? There’s a long history of undervaluing the arts in this country. We’ve also seen a significant erosion of arts and culture media. As Rosabel Tan and I found in our report ‘New Mirrors: Strengthening Arts and culture media for Aotearoa New Zealand’, commissioned by Creative New Zealand, “we are seeing a loss of specialist arts reporting and reviewing roles, as well as a reduction in capacity and confidence among other journalists to focus on this type of coverage.”

The most in-depth political arts coverage could be found on community radio station Wellington Access Radio via Austin Harrison’s Election Murmurs, featuring substantial interviews with the Minister and party spokespeople, and analysis from invited arts leaders. But without more arts reporting, arts and culture will remain absent from important political and national conversations. The Post’s André Chumko (who single-handedly produces much of New Zealand’s arts reporting), reflects in New Mirrors that stronger arts media:

would mean many more sets of eyes looking at annual reports, more mouths and people firing questions up to press secretaries and asking ministers, what are you doing about artist pay? What are you doing about these issues that artists are facing? It would mean greater scrutiny on the arts, which would improve transparency and accountability.

Labour’s biggest arts move this term was to significantly increase Te Matatini’s funding by $34 million over two years to grow Kapa Haka nationally (also a big win for Te Pāti Māori, who had pushed for equitable funding). It was great to see the championing of this popular policy, which followed a highly successful competition in Tāmaki Makaurau. While there was no Budget boost for Creative New Zealand, the last of the Government’s Covid recovery money for the arts sector ($22million that had to be spent up this year) was funnelled through CNZ to support festivals and artists.

Having acknowledged last year that Creative New Zealand’s arts funding systems weren’t working for the sector, CNZ undertook consultation and in November announced a radical shakeup of many of its funding programmes. “We’ve moved from a focus on investing in projects to investing in people”, signalled Gretchen La Roche, Arts Development Services Senior Manager. While the details of the new programmes are promising, meaningfully responding to artist needs and different career stages, for the time being it is a different way of distributing a diminishing pot of money.

There’s a huge demand for arts funding, reflecting a huge ammount of creativity activity happening in Aotearoa. CNZ’s final ever arts grants round had a success rate of 22%, with 193 projects receiving $7.8m out of a total 846 eligible applications requesting $36m. CNZ has warned that “there will be less pūtea to support the sector next financial year and beyond than in recent years.” The funding CNZ gets from the New Zealand Lotteries Grants Board is also changing – from a percentage of Lotto sales to a set amount, which is expected to result in a $9million reduction compared to the previous two years of funding. Reducing reliance on lotteries would be a good thing, but only in tandem with increased public investment.

CNZ’s new programmes offer a positive long term direction of travel (if it’s people we’re investing in, then the long-term goal must surely be an artist’s wage). With an emphasis on outcomes, the programmes are designed to collect evidence for the value of investing in the arts. But until such a time as there is sufficient funding, the arts sector remains trapped in the current cycle of crisis.

It is worth remembering that more New Zealanders than ever understand and support public investment in the arts. It is also worth remembering that Creative New Zealand is hands off from the Government by design, making its funding decisions without political influence. I mention this because this year we’ve again seen attempts to politicise funding decisions and stoke culture wars.

Act Leader David Seymour and right wing media led deeply cynical attacks on poet and playwright Tusiata Avia and Creative New Zealand’s funding of Auckland Arts Festival’s The Savage Coloniser Show. Avia recounted what happened on her Substack in ‘David Seymour and Me’ (Part 1 and 2): after Stuff published a video of Avia reading her 2019 poem ‘The 250th Anniversary of James Cook’s Arrival in New Zealand’ (published in 2020’s The Savage Coloniser Book, the basis of the stage adaptation), Seymour said the Government should “declare it will give nothing to racism, and withdraw the funding”. “Hang on a minute,” writes Avia, “how does a show about racism become accused of being racist?” Seymour outrageously compared the poem to the 2019 Christchurch Terror attack. The Platform’s Sean Plunket also went on the attack. Avia received horrific abuse and a death threat from a white supremacist.

There’s much shameless hypocrisy here of course. Seymour, the defender of free speech, trying to shut down an artist’s freedom of expression (and willfully misleading the public around the Government’s role in arts funding). Seymour, who told others to lighten up after joking about blowing up the Ministry for Pacific Peoples. Complaints to the media council arguing the original poem incites racial hatred were rejected: “The poem is undoubtedly a work of art and should be treated as such, it’s not a manifesto or plea for real-life violence.”

Anjula Prakash’s review of The Savage Coloniser Show affirmed that the show’s poetry “is generous and offers insights, often opening a door into the writer’s personal realm, though it is still a place that reflects ourselves back to us.” Anjula’s review is worth reading for its passionate defence of the production against the spurious political attacks:

It came to my attention before the show that the contents of the poem ‘250th anniversary of James Cook’s arrival in New Zealand’ caused a stir amongst some politicians like ACT party leader David Seymour who took a literal reading of the poem and claimed it might incite violence. If you so choose, you can look into the details of the incident. And even though I don’t think much time or attention should be spent on this issue, I still feel that some discussion should take place because it’s a reflection of the problems we still face in our day to day lives. No, brown women driving around in SUVs and beating up people is not a thing. It will never be a thing. And maybe if examined more closely, one could see what actually fuels hate crimes, and why it’s not a poem, or a play, and won’t ever be racially disgruntled brown women cruising around in a big car. At least the humour in the poem was obvious in performance as it got laughs from the audience at the punchlines.

The Savage Coloniser Show is honest, disruptive, and empowering as we are taken on a journey, through a landscape, and several perspectives. Painful and buried racism in our history is dug up, displayed, and pulled apart. The effects of colonisation are brought to the fore and set alongside our dysfunctional present so that we may draw lines between them. The reward for an unapologetic approach to the subject is catharsis for the audience, or unprecedented insight. Anyone who resides in this country is sure to see a part of themselves in the show.

The Savage Coloniser Show is in-demand on Aotearoa’s Festival circuit, touring to Wanaka Festival of Colour, Nelson Arts Festival and Tauranga Arts Festival. I can’t wait to see it at the Aotearoa Festival of the Arts in Wellington in the new year!

The ACT Party, now in Government, attacked Avia and Creative New Zealand again after Avia became the first Pasifika woman to receive the poetry award in the 2023 Prime Minister’s Awards for Literary Achievement (administered by CNZ). Act’s arts spokesperson darkly warned, “With a new Government looking to make spending cuts at low-value departments, Creative NZ is tempting fate.” So, we have a party in the Coalition Government (and a future Deputy PM-in-waiting) trolling a respected artist and threatening the independence of CNZ.

Mercifully perhaps, arts policy was absent from National’s respective coalition agreements with Act and New Zealand First. But without an arts policy from National, it is unclear where exactly the Government stands on key issues. Finance Minister Nicola Willis has committed to Te Matatini’s $28 million funding boost, but will she extend it beyond the initial two year funding period? And what about the restoration of Auckland’s St James, a policy commitment from Labour?

We have a new Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage, Paul Goldsmith. Goldsmith told The Post that “there are no large sums of money waiting to be doled out.” Asked about the prospect of a national arts strategy, “Goldsmith says he’s in two minds on the matter; he doesn’t think the sector lends itself to “some mastermind in Wellington” deciding its future. “I’m more of the ‘let a thousand flowers bloom wherever it goes’ and concentrate on how government can make that work. But I’ve got an open mind.”

VALUES INACTION

As we close 2023, the plight of the Palestinian people weighs heavily on the world’s conscience. Following Hamas’ devastating attack on Israeli civilians in October, Israel responded with a military and bombing campaign described by the UN Secretary General as creating a “graveyard for children”.

Hossam Madhoun, co-founder of Gaza’s Theatre for Everybody, has been sharing his account of the Genocide in Gaza. From his entry on 18 December:

Writing this piece, around me intense bombing and shelling did not stop at all. Hundreds of people are being killed at this time. Maybe me and my family will be among them, who knows? All those who were killed, more than 22,000 human beings who have been killed during the last 55 days, did not know that they were going to be killed in this brutal way.

As a theatre person, I think of Rashed Al-Shawa, “the largest and most important theater and cultural center in the Gaza Strip”. Described as a “beacon of cultural vibrancy for over two decades, a place of performance, poetry, music, art and local engagement” it had been a vital community hub, a “welcoming space for all groups of people to rehearse, perform, and exhibit.” The building has been “completely destroyed”, so too, a creative community.

This month, Israeli forces raided the Freedom Theatre in the occupied West Bank’s Jenin refugee camp and detained artists, critics calling it “part of an effort to destroy Palestinian culture” Al Jazera reported that “the raid and ransacking of the Jenin Theatre have come as a huge blow to the community and the people who work there who viewed it as a safe place.”

What is the role of Aotearoa’s creative community in responding to these atrocities?

Over 1000 signed Artists of Aotearoa’s letter in solidarity with Palestine and calling for a ceasefire. Signatories included Jane Campion, Chelsea Winstanley, Tayi Tibble, Nigel Borell, Rachel House, and Chris Tse and “Muslim, Arab, Māori, Jewish, Indigenous, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, non-religious, Queer, People of Colour and Tāngata Tiriti artists, writers, researchers and cultural workers from across the motu.”

A collective of artists and activists took up the call from Palestine’s ASHTAR theatre to present the The Gaza Monologues, with Tigalau Ness, Moana Maniapoto, Kate Prior, Liv Tennet, Reb Fountain, Dominic Hoey, Tali, Chlöe Swarbrick, Julia Deans, Alison Bruce, Arahi and others performing reflections of Gazan Youth at the University of Auckland on 29th November.

An open letter to Aotearoa’s cultural institutions from cultural workers, asked arts organisations “to stand by your values and publicly demand that our government call for a ceasefire.” It explained:

As artists we feel ashamed that nearly all of the museums, galleries, theatres, orchestras, festivals, publications, regional arts trusts, guilds and other arts companies across Aotearoa that represent, house, support and fund our work have not made any public statements that clearly and directly pressure our government to call for an immediate ceasefire at the very minimum, and standing in solidarity with the Palestinian people. When it comes to being critical and courageous for human rights, why does your bravery have boundaries?

… Our films, galleries, books and theatres are filled with historical stories of New Zealand resisting powerful international political systems in the name of justice, peace and freedom. Indeed, this is a cornerstone of our cultural identity on the world stage. We believe every cultural establishment in Aotearoa that protects this proud history should be considering how they utilise their name to continue that legacy and apply political pressure towards ceasefire.

Equity New Zealand’s board passed a resolution calling for an immediate and sustainable ceasefire in Gaza and Israel. Before the letter’s release, Basement Theatre posted “the suffering and loss of civilian life that we are witnessing on Gaza whenua in real-time is unfathomable. We want it to be known buy our communities that Basement Theatre strongly supports an immediate ceasefire, and we align ourselves with Aotearoa’s whakapapa of standing up for peace on the world stage.”

Our cultural institutions could be taking a leadership role in resisting injustice, using the power of the arts to spread awareness and support social and political change. But few have taken public action on Gaza.

While a vastly different issue, the removal of arts patron James Wallace’s name suppression also revealed a lack of leadership from arts organisations. Convicted of indecent assault for incidents spanning over 15 years, public discussion of Wallace’s offending – and how it had gone on for so long – had been a long time coming. In my 2018 Year in Review I wrote, “a wider reckoning is perhaps yet to come…. the theatre and the arts community in general need to make a difficult examination of culpability with patronage.” In 2023, the reckoning finally arrived.

Dudley Benson, who was assaulted by Wallace, called out the complicity of the arts world in enabling Wallace’s offending:

Despite James Wallace being found guilty of indecent or sexual assault against myself and two other men, I still hear claims that his “minor indiscretions” should be shrugged off. That we can let this stuff slide, since he’s given so much money to artists and arts organisations over the years. I’ve also heard the view, often from the upper echelons of the arts world, that “we knew what we were in for” when we chose to meet with James Wallace. And I suppose that therefore, we deserved what we got. This twisted attitude suggests to me that these victim-blamers knew who Wallace really was, and what he was up to. They had the knowledge for years that this man was a creep at best, and super- predator at worst, and yet they chose to do nothing other than indulge in a bit of gossip.

What should have been an opportunity for arts organisations who had benefited from Wallace’s patronage to take a strong stand for artist safety and against sexual violence was missed. As I wrote for The Pantograph Punch:

The muted response from arts leaders so far has been telling; most are ducking to say they are no longer funded by Wallace. Jonathan Bielski of Auckland Theatre Company is one of the few leaders to offer a full-throated repudiation: “Wallace’s crimes are appalling, and I condemn them in the strongest terms.” Why aren’t more arts leaders stepping up? It is not acceptable for arts organisations to wait it out until the media coverage falls away, quietly remove his name, and make embarrassing weblinks go dead. Nor is it enough merely to denounce the demon, and say that you stopped accepting his patronage.

I suggested it should be easy to find anti-bullying and harassment policies on websites and read clear statements affirming zero tolerance for harmful behaviour. There’s an opportunity to move to more active harm prevention across the art sector. But we need our arts leaders to step up.

In tension is the contemporary community and consumer expectation that organisations should be values-led in words and action, and organisations’ self-preserving risk-aversion. An environment of financial precarity breeds a culture of timidity. As these issues demonstrate, bolder leadership is needed.

We’re not done yet! This year’s commentary is split into two parts. CLICK HERE for 2023 – A Theatrical Year in Review [Part 2 – The Shows].

SEE ALSO:

Theatre Scenes Theatrical Year in Reviews: 2022; 2021; 2020; 2019 ; 2018 ; 2017 ; 2016 ; 2015 ; 2014 ; 2013 ; 2012 ; 2011 ; 2010

Leave a Reply