You want us to do what? [by James Wenley]

Show Pony asks you to get naked. Providence asks for a pash. And Wake Less asks you to dinner… among other things.

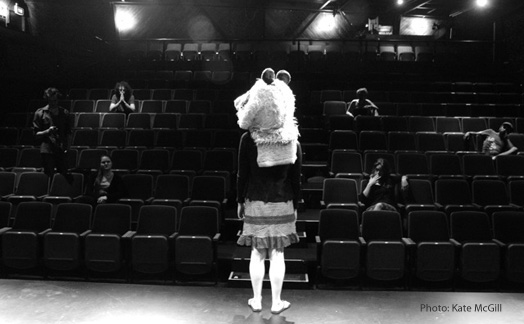

Three shows where the normal ‘rules’ don’t apply. Three shows where the audience is an important part of the performance. Three shows that made up for one intense, beguiling, perplexing, invigorating, weird and wonderful night at The New Performance Festival.

I’m writing about all three of together as there were some interesting conversations going on between them. All three were two-handers, in the sense that there were mostly two performers onstage, whose interaction and relationships were important. But these relationships are complicated by the role of the audience within the performance. Our normal theatre contract – we watch, they perform – is waived. In these shows, spectators become participants. Wake Less warns: “As an audience member at a Binge Culture performance, you can expect to be included. You might be questioned, teased, looked in the eye or invited to save a pod of whales.” Are you brave enough?

This isn’t anything *new* of course – the spectre of the ‘passive’ audience member has long been challenged. Actors will tell you the mood of an audience (different each night) has a direct influence on their performances. A lot of theorising and experimenting went on in the 20th Century for instance, from names like Brecht, Artaud and Grotowski about just what the role of the audience might be and should be. Grotowski saw the very essence of theatre to be the actor and the spectator, with theatre being “what happens between them they are united – theatre is their rapport with each other”. Those moments of being ‘united’ are what I live for in theatre – think of moments when audiences collectively take an in-breath, caught up in the drama. But often, we do in the darkness, in the comfort of our seats. We like being there. There’s often a definite cringe factor involved when the lights come up and asked to participate. Sometimes there’s a brave soul who leaps at the chance, but if the audience member doesn’t want to be there, it’s uncomfortable for all. It’s interesting to see how these three shows then invite participation – do they create a rapport? Are we united?

Immediately front and centre (and generally all over the stage) of Show Pony are its creators and performers Alexa Wilson and Nisha Madhan. Loosely exploring obsession with celebrity culture, the show is mutual love-fest between the two performers (and their many fans in the audience). At the top of the show they introduce each other to the audience over and over again, each rushing out to take their ‘entrance’ down the staircase with a self-mocking air. They are a great match; Alexa is a stunning creative creature, ‘famous’ for using her naked body in her performance work. Nisha, a fabulous actress, (who can do a great ‘Beyonce’) is famous for being on Shortland Street. Introductions, and dancing done, they settle on the couch for a chat show talk about their life and work. An audience member, who they know by name, is asked to hold up different signs with instructions for us, and we bark, boo and do Mexican waves. There’s a clear division here – the audience actions are often at odds with what’s happening onstage. The audience ‘volunteer’ is made to sit down for upstaging the performers.

They get to discussing Alexa’s body of work, or rather her body in work. She says she feels hidden when naked onstage – we are not looking at her, but her body. It’s an interesting area of discourse that is returned to throughout the work. Nisha is challenged to ‘play’ Alexa and re-enact dance work Rainbow Warrior 2011, in which Alexa appeared naked, painted like a rainbow. The actual work, which appeared in Love Me at Galatos, was a powerful piece – but here it’s confusing, especially for my friend seeing it without context. This section, like most of the initial part of the show, has an ‘in-side joke’ exclusive feel, as if designed for those ‘in the know’ (of which, there were many).

The show begins to go down some interesting wider avenues; the pot plant (ubiquitous in chat shows) begins to communicate and give instructions to the performers. They take a break, Nisha sitting amongst the audience, Alexa going up the stairs and back down with a person she had found at the bar. One male audience member is called up, and has a John Key mask placed on him, and then a Gorrilla mask. He sits passively as Alexa and Nisha do a politically and erotically charged dance and seduction takes towards him. Social Media narcissim gets a go-over, and they end by answering telepathic questions from the audience.

The celebrity obsession and vacuousness of our culture is a premise dripping with potential, and I would have liked to seen further exploration of this theme. There’s much play with the audience, and people the performers personally know are called out too, a recognition of us, but the performers dominate. There’s a rapport, but it’s mostly one way. We are there as medium for them to perform.

At one point, Nisha and Alexa ask for an audience member to come up and get naked. The audience looks horribly uncomfortable. They look us over, they hold up shirts we can win as prizes. We look down, pull back in our seats. The moment passes. They probably never expected anyone to do it – but what would if someone had?

A beautifully simple, and quite unexpected moment, is the bopping of balloons between performer and audience, a demonstration, perhaps, of the give and take of the performance event.

We’re heartily invited by the actors into the next space for Providence, which is covered with cardboard boxes and paper. The Actress identifies herself as Tamsin, and begins to tell us a story. Her fellow performer (Ken) busies himself amongst the cardboard, collecting and making things. I find her story difficult to grasp and follow (it does include some interesting commentary on the right way to punch someone). The two take turns to monologuise, before, like Show Pony, saying they are going on a break. The actors, however, leave us completely, opening the doors to the world outside and disappearing. We are left to our own devices. My friend takes this moment to ask me, if I met an Alien, how I would describe the difference between a cat and a dog. Other people wait silently. What’s going on?

Providence, from writer/director Louise Tu’u is about states of homelessness, the structure of the performance meant to emulate “the dysfunction of the characters’ lives, all the while playfully undermining traditional script-writing conventions”. Without this context, I think I would have struggled to figure it all out, and even with the context, haven’t really. There are hints of drug use, ambivalence to the world, pain, a brother/sister relationship in breakdown, but I find it very difficult to sense out.

The successful scenes get our buy in: a large cardboard box (standing for an expensive Grey Lynn house) is put up for auction – and we recognise and know how to play this game. Each time we put our hands up and bid, the actors fall to the ground – the actors are simultaneously in control, and controlled by us. Another game is played between the actors as they point to different things in the room, claiming them as ‘mine’, and then bagsing bigger and bigger things outside the room (“I bags Japan”), addressing issues of ownership clearly and effectively. A further game is played when they write on and hold up signs (a theatrical device we’ve already seen of course in Show Pony, but wider resonances here from their use on the street). Ken wonders by with a sign asking for a pash. Several ladies shake their heads, but one audience member is game, and lips lock. He’s stoked. Signs aren’t shared with all the audience however, and we feel like we’re missing the joke when other’s laugh and we can’t see it. Granted, there seems to be a point here about sharing, and who can get what, but in my corner I felt like I was missing out on quite a bit.

The play ends with the rubbish being ordered and cleared away by Ken, Tamsin rescuing what she can, protecting them on the floor, curled in the fetal position. Ken exits, and she remains on the ground. Nothing happens. The music run outs. Still nothing happens. The audience is restless, looking at each other. The assumed theatre contract seems to be that performers will let the audience know when it is time to clap – either with a strong ending, or by breaking out of character. Are we meant to really consider this image? What does it say – Tamsin so strongly clutching her detritus? Is she dead? Eventually, there were claps, and the actors take their bows. But it was a puzzling conclusion to a puzzling play.

I felt like I was missing something obvious, that there was a huge element of the show that I was just not getting. But without any ‘rules’ set-up for an audience, we didn’t know where we were, or where we going. The rapport was fleeting.

We didn’t know where we going in Wake Less either, but in that show, that was very much part of its pleasure. Our first encounter is with an actor we later learn is called Simon. He enters wearing a shirt tucked in to his shorts, knee high socks and a big nervous grin. We stare at him, he stares back. He crosses the room, opens a door looking for something, and then draws his attention back to us. We look on expectantly. He’s listening to us, reacting to coughs and noises. He gets close to an audience member – they lean forward, he steps back. The game is played with the actor and the audience, each reacting to what the other is doing. It’s a simple, child-like, clownish and fun routine. Just as I find Simon staring at me, another actress (Isabel) bursts in the door, apologising for being late. She apologises too for Simon’s behavior – we stared him, as if expecting something, so of course he was going to play up, he was only trying to give us what we wanted. But what did we want? She goes behind a large screen, and our game continues. Simon asks us to do something almost unheard of in Auckland theatre – swap seats. And we do it with glee – its subverting authority, and messing with the new actress. Yes, we’re completely aware that it’s not really going to fool Isabel who as rehearse actress knows exactly what to expect, but we find it fun to pretend. She comes and goes again, talking away, oblivious to our switch. Simon now gestures for us to stand up, and join him on the ‘stage’. Isabel returns to find her way blocked by our bodies, seats vacated.

She helps us to find our seats again, and the ‘play proper’ begins – a familiarly conventional play, somewhat satirising Roger Hall’s Four Flat Whites in Italy (which hey, I liked!), about a middle aged couple deciding to go on holiday abroad after the husband Reg is made redundant. But then they stop, tiring of it. Isabel asks us “Would you like to do something different?”, which is the catch-cry of the Wake Less. The show goes down many different strange avenues and dreamlike scenes – there are recurring, sad masked figures, a dinner party where invited audience members are asked to give speeches on topics like “What is happening in the Middle East”, Isabel delivers a towel to an audience member she says is having a baby.

And we are willing to go and follow them everywhere they go, even to Gaza and back. This is partly because Simon and Isabel are such warm and charismatic performers that we really want to be their friends, but also because of the sense of equality and community formed from the beginning. Our rapport. We trust them, we feel like we are going on the journey together. There’s far more that I could write about why I enjoyed the show, but needless to say I’ll be keeping an eye out for the next show Binge Culture Collective bring to Auckland.

The New Performance Festival is now over, but over its 9 days it was an exciting mix of different experiences – hopefully you managed to catch some of! For me, Call Cutta in a Box and Wake Less were the stand-out experiences. Both required as much from the audience as the performer to deliver a great show. Both are nominally ‘new performance’, but really is old performance – a conversation – dressed up in a different way. And they both constantly seek and succeed in surprising you.

The compact festival was great for concentrating the buzz, but I wasn’t able to get to as many shows as I’d have liked – some were only on for one night – and certainly some shows were deserving of longer runs and the benefit of word of mouth. Audience numbers seemed to vary between shows, and there’s still work to be done in fostering awareness and appreciation of these ‘non-traditional’ types of shows. It’s a very exciting development for Auckland theatre, and I hope it continues. Both for the conversations between shows, and the fascinating post-show discussions about what we’d experienced.

The New Performance Festival was presented by THE EDGE and curated by Stephen Bain. It closed on the 25 February.

SEE ALSO: Theatreview review of Show Pony by Nik Smythe, and Providence by Vanessa Brynes

Leave a Reply