I’m on it [by Matt Baker]

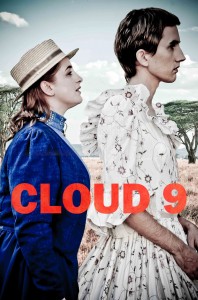

Cross-gender and cross-racial casting, an era-specific time relocation, and characters represented by dolls or never seen at all are three fundamental theatrical constructs employed by Caryl Churchill to present the themes of sexuality, oppression, and identity in her 1979 play, Cloud 9. Such constructs illustrate said themes to the audience in a blatant and purposeful way, but it would be wrong to consequently conclude that the play is in any way easy to perform or direct. Director Sam Shore dutifully honours the themes and motifs by tackling the play head on with an ensemble of eight incredibly charismatic and versatile actors – versatility being a key component.

While each actor is double cast between the two acts, having one character which resonates with them more so than the other, Stephen Anthony Maxwell shines as both Betty and Edward. Maxwell brings a broken quality to Betty, juxtaposing the fluidity of his movement, and pitches his performance with the right amount of necessary melodrama while maintaining an emotional truth. As Edward, he brings a weight which echoes the emotional trauma of act one.

Likewise, Donogh Rees’ Victoria in act two carries all the baggage of suffering at the hands of an oppressive father and oppressed mother as a doll-like child from act one. As her own grandmother, Maud, Rees has a self-appointed regality, and shrewd observational skills which are revisited, albeit briefly, in act two.

Renee Lyons does not hold back as the titillating Mrs. Saunders, providing the play’s physical comedy, and maintains a steady strength as Lin, while still allowing for an emotional journey.

Jacque Drew, who contrasts Maxwell by playing Edward then Betty, gives an earnest portrayal of a young boy struggling to find his identity and express his true feelings. One’s natural instinct might be to compare Drew’s Betty with Maxwell, however, there is a great enough shift in the two worlds of acts one and two in the writing alone to avoid any such comparison.

The female cast of actors is rounded of with Genevieve Cohen as Ellen and Lin’s brother in the first and second act respectively. Ellen, unfortunately, is a functional and under-written character, whose moment of reveal is not earned by Cohen through her few appearances prior.

Francis Mountjoy gives a steely performance as Joshua, a slave devoid of obsequiousness, reminiscent of Samuel L. Jackson in Django Unchained, but without the sardonic insubordination. Mountjoy finds a great contrast in Gerry, with a much more relaxed, if not misanthropic, attitude to life.

David Capstick is absolutely committed to the role of Cathy, never once steering into Fremdschämen, which could easily be the case with a less talented actor. Capstick gives a total physical, vocal, and mental wholeness to his performance, while conscientiously serving his fellow actors without scene stealing.

The only character who seems mishandled is Capstick’s Clive, whose slightly buffoonish portrayal takes away from the very real danger and oppression which the character represents. Similarly, while Joel Herbert’s innate intelligence as an actor lends itself well to the befuddlement of Martin, a greater – and darker – contrast is required for Harry.

Musical director Alex Taylor, who also performs as pianist and violinist, has composed a variety of numbers, which work best when hitting minor chords, echoing the dangers in the play. With Rachel Wells (cello), Emma Fetherson (viola), and Samantha Dench (flute), the band collectively serves the work in a professionally inconspicuous manner.

Isobel Dryburgh’s set design gives the feeling of an extensive landscape in act one’s colonial Africa, and focuses the attention to the confined surroundings of a park bench in act two’s modern London. The smell of grass and dirt is an excellent sensory element. Lighting by Ruby Reihana-Wilson is nicely both maintained and accentuated when necessary.

The two acts are distinctly different, and while the first could stand on its own, the second requires the seeds that are sown in the former. Act one’s melodramatic style is reminiscent of Shakespeare’s comedies, with secret lovers and numerous entrances and exits. Act two feels to be very much a product of its time, and, although I understand Shore’s explanation that the themes are timeless, I don’t agree with the complete modernisation of the act. Sexual oppression, specifically that of women, while relevant, is simply less prevalent than it was in the late 1970s. Regardless, both Shore and his cast address Churchill’s material with great clarity.

Cloud 9 is presented by Good Company and plays at The Basement Theatre until 13 April. Details see The Basement.

Leave a Reply